Does a person experience time, or does one simply travel through it as if it’s some kind of elongated underground tunnel through the earth? Fox Rich’s tunnel allows for a modicum of speed and is beset with dramatic twists and turns. The tunnel of her husband Rob, meanwhile, is a monotonous straight line that must be passed through with inconvenient lethargy.

Back in 1997, the pair ran a hip-hop clothing store in Shreveport, Louisiana that had fallen on hard times. Their emergency scheme to financially underwrite the business involved an armed robbery: her keeping the engine running outside; him carrying out the deed. They were both caught and received custodial sentences: her 19 years (of which she served three); him an unnecessarily draconian 65 years without parole.

It’s a brutal illustration of the American prison industrial complex and how justice often takes the form of retribution and example-setting when it comes to people of colour. Cherishing freedom with near-rhapsodic intensity, Fox then dedicated her life to having her husband’s sentence commuted. She wanted that long, straight, slow tunnel to break out into the light much sooner that the law would allow for. She documented her efforts on camcorder, and that’s where director Garrett Bradley comes in.

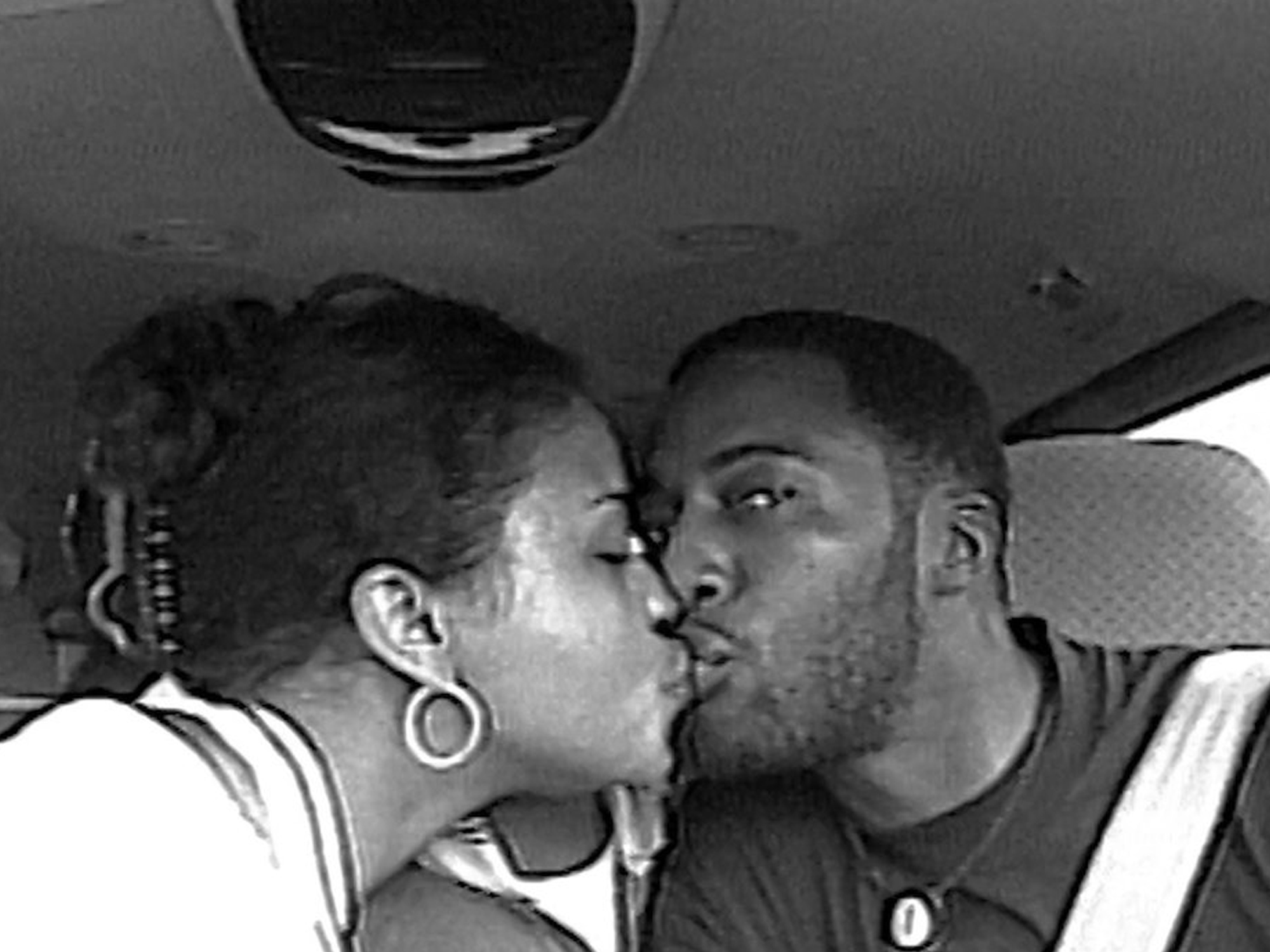

The title of her film, Time, alludes to the slang term for a prison sentence, but also to life’s most fragile resource. In just 81 minutes, she compresses 18 lost years into which Fox employs her overflowing stores of moxie to do everything in her modest power to be able to recreate a simple, filmed image of herself and her husband, sitting in the front of their car, smiling and kissing.

Read next: Garrett Bradley on the invisibility of the prison industrial complex

Meanwhile, she is raising six children and making sure they are fully aware of what she’s fighting for and how they might be able to assist in the future. This remarkable film comprises snatched domestic scenes, often tragicomic, in which Fox does not allow a minute of her precious time to slip away from her unused. When she’s not corralling her sweet boys, she holding crowds rapt at a public address, or just making calls to anyone and everyone, trying to locate the tiny chink in the armour of this daunting bureaucracy of mass incarceration.

Bradley toys with chronology and flits back and forth in time, constantly reminding the viewer, via Fox’s change in physical appearance, just how long 18 years is. She also emphasises connections through montage, as Fox makes the same emotive and articulate plea at speaking engagements and she’ll appear noticeably older in some more than others. The evocative use of the tinkling, fragile piano music by Ethiopian “singing nun” Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou is a masterstroke of context, linking these black-and-white images to some bygone era, making the film feel like the lost reels of a silent classic.

There’s even a sense that the film exists to fill in the blanks for Rob – these captured images offering a remembrance of lost time. If there’s one criticism, it’s that later in the film, when Fox gravitates ever closer to her objective, the modern score by Jamieson Shaw and Edwin Montgomery perhaps works the heartstrings a little too hard and heavy. Mostly, though, this is a staggering portrait of resilience against insurmountable odds.

The post Time appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments