Max Richter’s work, even at its most expansive, is inward-looking and unafraid to operate from a place of vulnerability. This was personified by the influential contemporary classical composer’s 2015 record ‘Sleep’, an eight-hour concept album which is built around various tonal shifts that synch to the frequencies on which the human brain operates while we sleep.

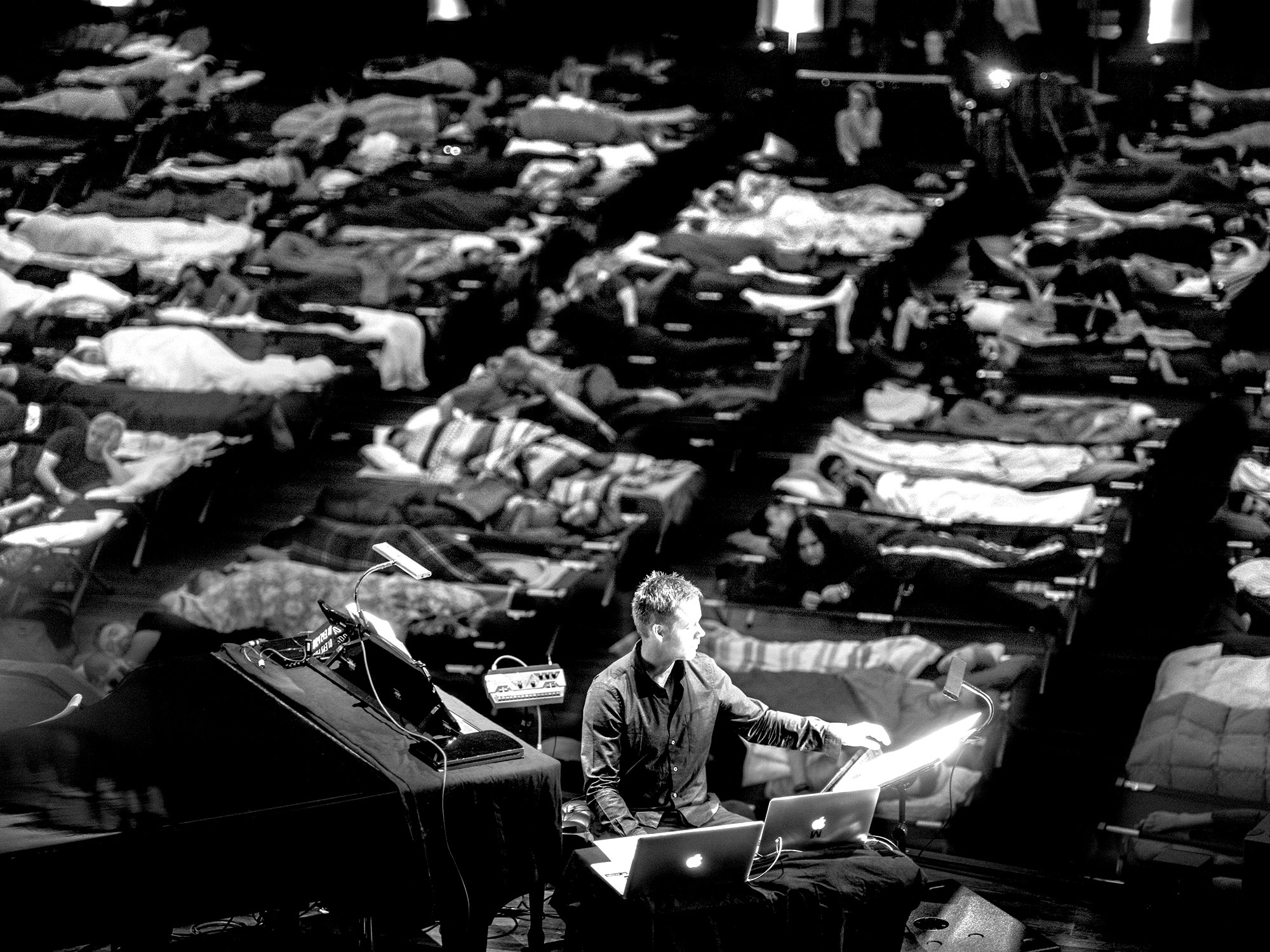

Richter even conferred with neuroscientist David Eagleman to ensure his music could leave an impression on its listeners while they snoozed, with each of the Suites designed to be experienced while in both conscious and unconscious states. This documentary from director Nathalie Johns delves even deeper into the creation of ‘Sleep’ and its unique song cycle – it transports us to one of Richter’s pioneering live shows in Los Angeles, where every concertgoer is given their own bed to experience the album as it’s played in its entirety from dusk through to dawn.

At a time when the world appears to be teetering on the edge of calamity, swinging violently from one disastrous news event to the next, there’s something cleansing and therapeutic about this film, particularly the way in which it prioritises the concept of taking time for yourself. Richter describes ‘Sleep’ as being a “quiet protest” designed to help people “step off the wheel and take stock.” This does happen to conveniently mirror much of the philosophical questioning and interior thought that has been a direct result of the prolonged, hibernation-like Coronavirus lockdown.

Even though this film exists in a world before social distancing, it embraces the idea of moving away from the overly-complicated trappings of globalisation and creating a powerful prescience. Beyond this meta-commentary, it also works as a three-dimensional account of Richter’s drive to radically alter the conventions of popular music, whether through how it’s played live or recorded in the studio. “I don’t want people to just listen to ‘Sleep’, I want them to experience it like a landscape. They should be inside of it,” the musician, who abides by a near-scientific attention to detail, powerfully explains at one point.

One obvious weakness of the film is the over-used reflections from people in the LA crowd, which can sometimes veer into indulgent territory. Another criticism, perhaps, is that beyond insisting this experience is overwhelmingly meditative, there doesn’t seem to be much hunger to probe the idea that Richter’s concept could in fact exacerbate our fears of losing control of our bodies, or even be seen by some as a gimmick.

Yet in a world where so many of us are happy to be led and defined by technology, the way this film explores the idea of how control can be channelled into something more positive, is fascinating. Even though live shows might be off the cards until 2021, Johns’ film, which has a hallucinatory feel to its cinematography and pacing, suggests Richter may have unearthed a new dawn for communal, music-led experiences. The filmmaker and her subject are acutely aware that there’s never been a better time to switch off and be still.

The post Max Richter’s Sleep appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments