One of the things we often get asked at Little White Lies is how we decide what to put on the cover of our magazine. Well, there are numerous boring logistical factors we have to consider, but I like to think that our approach is ultimately more idealistic than pragmatic: is this a film we’ll look back on 10 years’ time and think, yep, that was a good ’un.

The 2010s was the first full decade in the magazine’s 15-year history. We’ve seen a lot of great movies in that time, and although we don’t always get it right, I can honestly say that looking back at the past 10 years of LWLies – 56 issues in total – has reminded me why I fell in love with cinema (and magazines) in the first place.

But this list was not made purely for sentimental reasons. I wanted to take this opportunity to bring together some of our most cherished contributors past and present, and find out which films have endured and why. What were the films that really meant something to the people who make LWLies what it is.

More than 300 films were nominated by some 70 writers, each submitting their personal top 10 of the decade ranked in order of preference. Our criteria was fairly open: films had to be feature-length, with a production year of between 2010-2019 (per IMDb), and released either theatrically or on a digital platform. To make things as democratic as possible, the final ranking was done on a points system, with an extra point awarded for each subsequent vote a film received.

We hope you enjoy this rundown of our favourite films of the decade, and that it inspires you to seek out some of the titles you’ve not yet had the chance to watch. When you’re done reading, be sure to share your own top 10 of the 2010s with us @LWLies – and if you simply can’t wait to scroll to the bottom of this page to find out what came out on top, you can check out the list at a glance. Here’s to the next 10 years. Adam Woodward

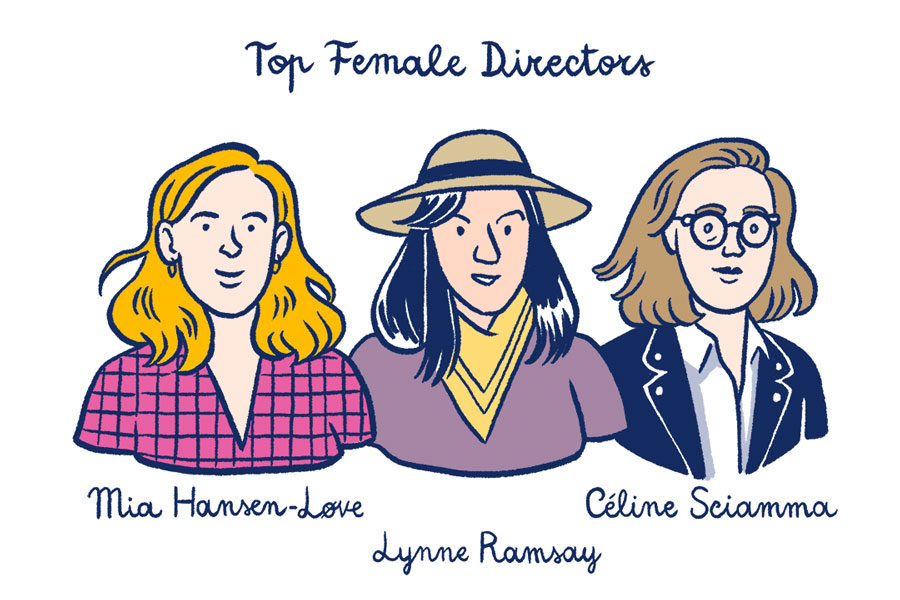

100. We Need to Talk About Kevin (Lynne Ramsay, 2011)

Lynne Ramsay’s disturbing 2011 feature made a star out of Ezra Miller, playing the titular Kevin opposite Tilda Swinton as his mother, Eva. This icy drama about a disturbed teenager is excruciating, uncomfortable viewing, confronting the same themes of maternity and nature versus nature as the novel, but propelled by the outstanding performances, and Ramsay offers no easy answers about the nature of evil. Hannah Woodhead

99. The Nine Muses (John Akomfrah, 2010)

An archive documentary-cum-essay film split into nine chapters, John Akomfrah’s beguilingly experimental bricolage is one of the most vital and original artistic responses to the subject of immigration that British cinema has ever produced. Pieced together with remarkable, allusive fluidity, The Nine Muses blends a dazzling array of sonic and visual archive footage, rendering it endlessly re-watchable. Ashley Clark

98. Bastards (Claire Denis, 2013)

It’s been a pretty decent decade for Claire Denis fans, as reflected by the fact she appears twice in this list. The first entry saw the French master unceremoniously relegated to an Un Certain Regard berth at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival (usually reserved for first-timers and lesser-knowns). More fool them: Bastards is an intoxicating modern noir which looks at the evil that men do through an unflinching lens. Adam Woodward

97. Eighth Grade (Bo Burnham, 2018)

A certain degree of scepticism comes with any coming-of-age comedy about teenage girls headed by a male filmmaker, but Bo Burnham’s directorial debut bucks the trend. Powered by an incredible performance from Elsie Fisher, this sweet story nails what it’s like to grow up in the age of the internet. Capturing romance, anxiety, heartbreak and hilarity within 90 minutes, it’s a balm for the soul, as essential to Millennials and Zennials as John Hughes was to Gen X. HW

96. The Work (Jairus McLeary, Gethin Aldous, 2017)

The Work is unlike any prison film you’ve seen before. Co-directors Jairus McLeary and Gethin Aldous take viewers inside America’s notorious Folsom Prison – specifically, a single room where inmates participate in a group therapy session over four emotionally-fraught days. It’s a refreshingly non-judgemental, frequently raw look at the process of rehabilitation. AW

95. Manchester by the Sea (Kenneth Lonergan, 2016)

Margaret might be the critical darling of Kenneth Lonergan’s small but substantial filmography (as its placement on this list testifies), but it’s Manchester by the Sea that established the New Yorker as one of America’s best directors. Casey Affleck plays a man forced to reckon with an unspeakably horrific family tragedy, with Michelle Williams at her devastating best as his estranged wife. AW

94. Two Days, One Night (Jean-Pierre Dardenne and Luc Dardenne, 2014)

Belgium’s Dardenne brothers had a bit of a strange 2010s. The bubble or their rigorous, off-hand tales of suburban discord burst with 2016’s critical and commercial misfire, The Unknown Girl, while their latest, Young Ahmed, has yet to secure much distribution outside of France. Lucky, then, that this was also the decade in which they made their finest film, in which Marion Cotillard gifts the brothers with a career-best performance as a depressive mother attempting to keep her head above water. David Jenkins

93. Paradise Trilogy: Love / Faith / Hope (Ulrich Seidl, 2012-13)

In the era of 90 Day Fiancé, Ulrich Seidl’s Paradise: Love feels prescient, especially in its fluid and natural shooting style, bordering on documentary. Teresa, a white woman, goes to Kenya to indulge in sex tourism, stirring up questions for me about colonialism and power. It’s an incredibly candid portrayal, showcasing the transactional aspects of her “relationships” and their dynamics. Part of an even greater trilogy, where Seidl’s protagonists envisions their own views of paradise. Tayler Montague

92. Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping (Jorma Taccone and Akiva Schaffer, 2016)

It feels quite rare nowadays that we get a genuinely original studio comedy, which made Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping stand out even more. This mockumentary from The Lonely Island follows a young musician (and possible Justin Bieber parody) called Connor4Real, who splits from his band The Style Boyz only to find out life as a solo artist isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. This Is Spinal Tap for the meme generation. HW

91. Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2015)

An anthropological expedition to the dark heart of the Amazon becomes a psychedelic odyssey in Colombian filmmaker Ciro Guerra’s transcendental deconstruction of Western imperialism and myth-building. Thematic allusions to Aguirre, Wrath of God and Apocalypse Now notwithstanding, this formally ambitious fever dream is a true original. AW

90. Goodbye First Love (Mia Hansen-Løve, 2011)

A Mia Hansen-Løve film is both emotional and restrained; she captures the unstoppable flow of time itself. Her characters go through intense pain yet are compelled to keep moving. Lola Créton is the conduit for this energy in Goodbye First Love. Her shy character, Camille, is shown in vignettes between the ages of 15 and 25 parsing her passion for the older, unreliable Sullivan. The ending is perfect. Sophie Monks Kaufman

89. Blue Valentine (Derek Cianfrance, 2010)

The ultimate anti-first date movie, Derek Cianfrance’s drama spans the course of a relationship from its blissful beginning to its bitter end. The scene in which Dean and Cindy go to a cheap motel in a last-ditch bid to save their marriage is utterly heartbreaking, but we’ll always cherish the thought of Ryan Gosling strumming a ukulele while Michelle Williams tap-dances in a doorway. AW

88. Goodbye to Language (Jean-Luc Godard, 2014)

French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard continues to reinvent cinema in his eighties. This experiment in 3D – shot with custom-built rigs using consumer-grade camcorders stuck together – featured mind-bending images such as the stereoscopic image puling apart and coming back together, and proved a confronting and innovative technical and philosophical exploration of the constrictions and liberations inherent in trying to communicate. Ian Mantgani

87. Silence (Martin Scorsese, 2016)

It may not boast the chest-thumping grandiosity of The Wolf of Wall Street or the epic metatextual scope of The Irishman, but this long-gestating passion project, about a pair of Portuguese Jesuit priests searching for their mentor in 17th century Japan, is arguably Martin Scorsese’s defining artistic statement of the last decade. An introspective, theological masterpiece from America’s greatest living director. AW

86. Good Time (Josh and Benny Safdie, 2017)

Practically levitating out of my seat, it was the moment I saw White Castle that I knew Good Time was the best film of 2017. The Safdies brilliance is in their ability to have me root for the imperfect laymen who do what they must to survive. In this particular case, the brother to brother relationship pulled right at my older sibling heart strings and made me want so badly for them to get to that little piece of paradise, by hook or by crook, bank robbing money in tow. TM

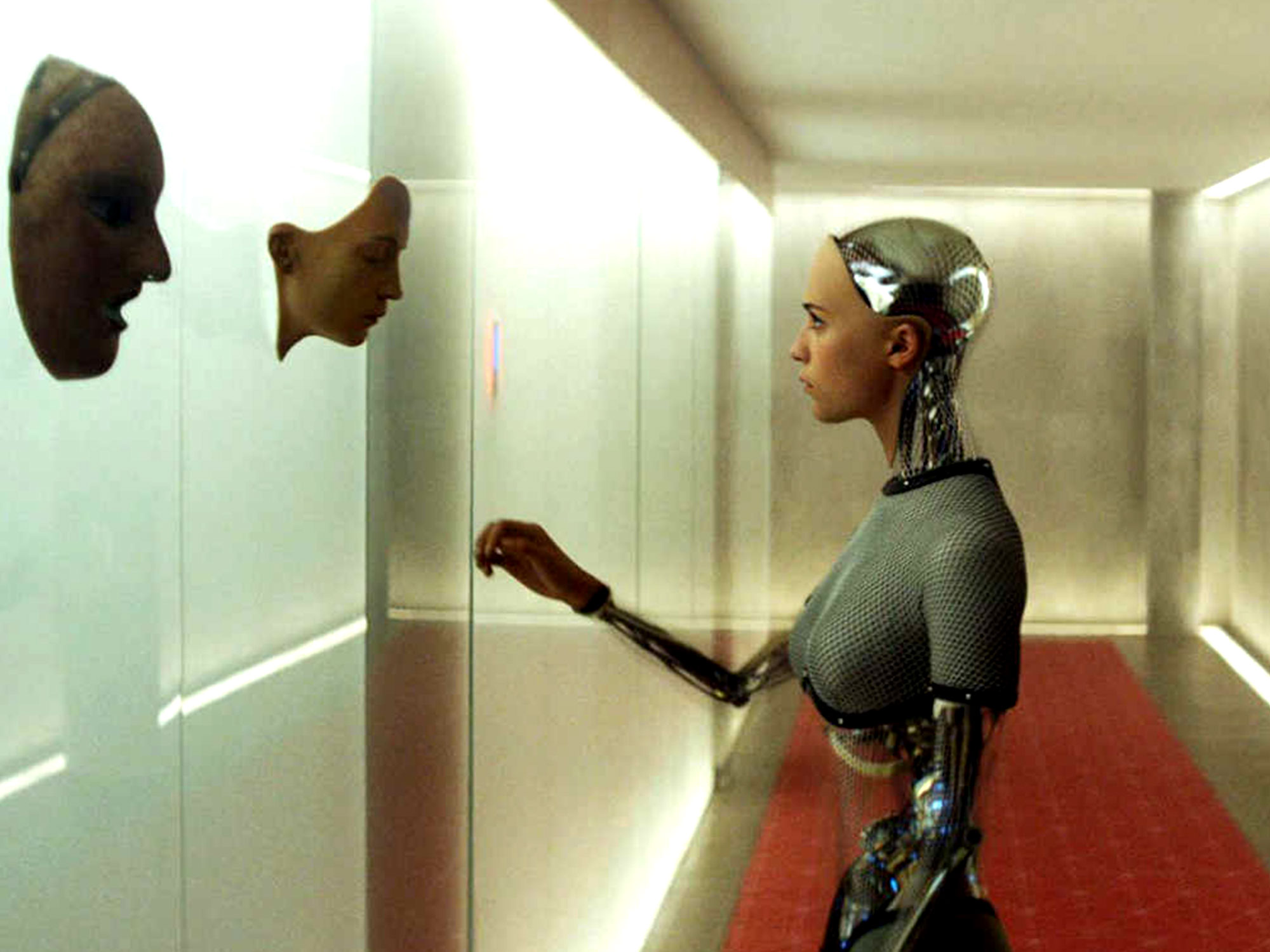

85. Ex Machina (Alex Garland, 2014)

A fresh take on an old question, Alex Garland made his directorial debut with a haunting examination of the human condition in a world of advanced Artificial Intelligence. A breakout role for Alicia Vikander, and strong performances from Oscar Isaac and Domhnall Gleeson, this sleek sci-fi thriller is as beguiling as the machine at its heart. Emma Fraser

84. House of Tolerance (Bertrand Bonello, 2011)

Booed when it was initially unveiled at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011, House of Tolerance has not only risen up the ranks of French director Bertrand Bonello’s own personal cinematic corpus, but is also now placing on best of the decade lists across the globe. The film offers an ethereal take on late 19th century lives of the working women in a Parisian bordello, with bold stylistic liberties taken in order to tether the story and its politics to the present day. DJ

83. Enemy (Denis Villeneuve, 2013)

Denis Villeneuve has contributed hugely to the past decade in cinema, but perhaps most overlooked is his desperately moody take on Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Double. Starring Jake Gyllenhaal cast (twice) in the kind of hammy role that he seems to relish, Enemy is a deceptive, dreamy jump from reality with a brain-crumpling final act. Beth Webb

82. Mysteries of Lisbon (Raoul Ruiz, 2010)

No one but Raul Ruiz could have pulled off this grand four-hour cinematic tapestry lush with palace intrigue, shifting memory, and carnal lust set in 19th century Portugal. The master Chilean filmmaker would pass away soon after the film’s expanded release in the United States, which added a certain supernatural melancholy to watching a masterpiece already rife with haunting historical spectres. Glenn Heath Jr

81. Nocturama (Bertrand Bonello, 2016)

Bertrand Bonello scared off Cannes’ selection committee with his vision of youthful unrest, a work that refuses to condemn the elaborate terrorist plot carried out by a multiracial crew with unclear motivations in the first hour. But the final stand that fills the second suggests a tragic eulogy for radicalism, in whatever form it may take. Charles Bramesco

80. Horse Money (Pedro Costa, 2014)

The ghosts of Portugal’s colonial past haunt Pedro Costa’s elliptical study of cultural erasure and repressed collective memory. Following a Cape Verdean immigrant named Ventura (who first appeared in Costa’s previous narrative feature, Colossal Youth, and also stars in 2019’s Vitalina Varela) as he navigates Lisbon’s dingy, decaying urban centre, Horse Money is a singular requiem for the marginalised and systematically oppressed. AW

79. Pariah (Dee Rees, 2011)

“I am not broken, I am free.” The first time I saw Adepero Oduye’s unforgettable face was as Alike, “the other one,” in Pariah. The best aspects of her performance are within her facial expressions, a sly smile or laughter as a means of belying an undying need to want to be herself. The self she has to suppress or is seeking to find is that of a young Black queer woman. This identity and navigation of how she best fits within it puts her at odds with her mother, who very much disapproves of her daughter’s sexuality. TM

78. Kill List (Ben Wheatley, 2011)

For his alchemical second feature following the DIY gem Down Terrace, Ben Wheatley took the base materials of a bargain-bin Brit-crime thriller – bickering assassins, urban grime, a scowling Neil Maskell – and spun them into gold. Semi-improvised by a flawless cast, Kill List is bracingly bleak, alarmingly funny and utterly terrifying. Tom Huddlestone

77. Certain Women (Kelly Reichardt, 2016)

Kelly Reichardt’s trio of short stories from rural Montana studied the internal lives of women dealing with the emotional baggage of themselves and others. Underplayed, rich, subtle and quietly devastating, it featured masterfully internalised performances from Michelle Williams, Laura Dern, Lily Gladstone and Kristen Stewart, and is so vividly realised you can smell the cold mountain air while watching it. IM

76. Girlhood (Céline Sciamma, 2014)

Céline Scammia’s shimmering account of working class adolescence is crystallised in a moment that many use to define a whole generation of cinema. Four girls, draped over each other in a state of blissful affection, moving through a hotel room’s blue light to Rihanna’s bassy anthem ‘Diamonds’. Perfection. BW

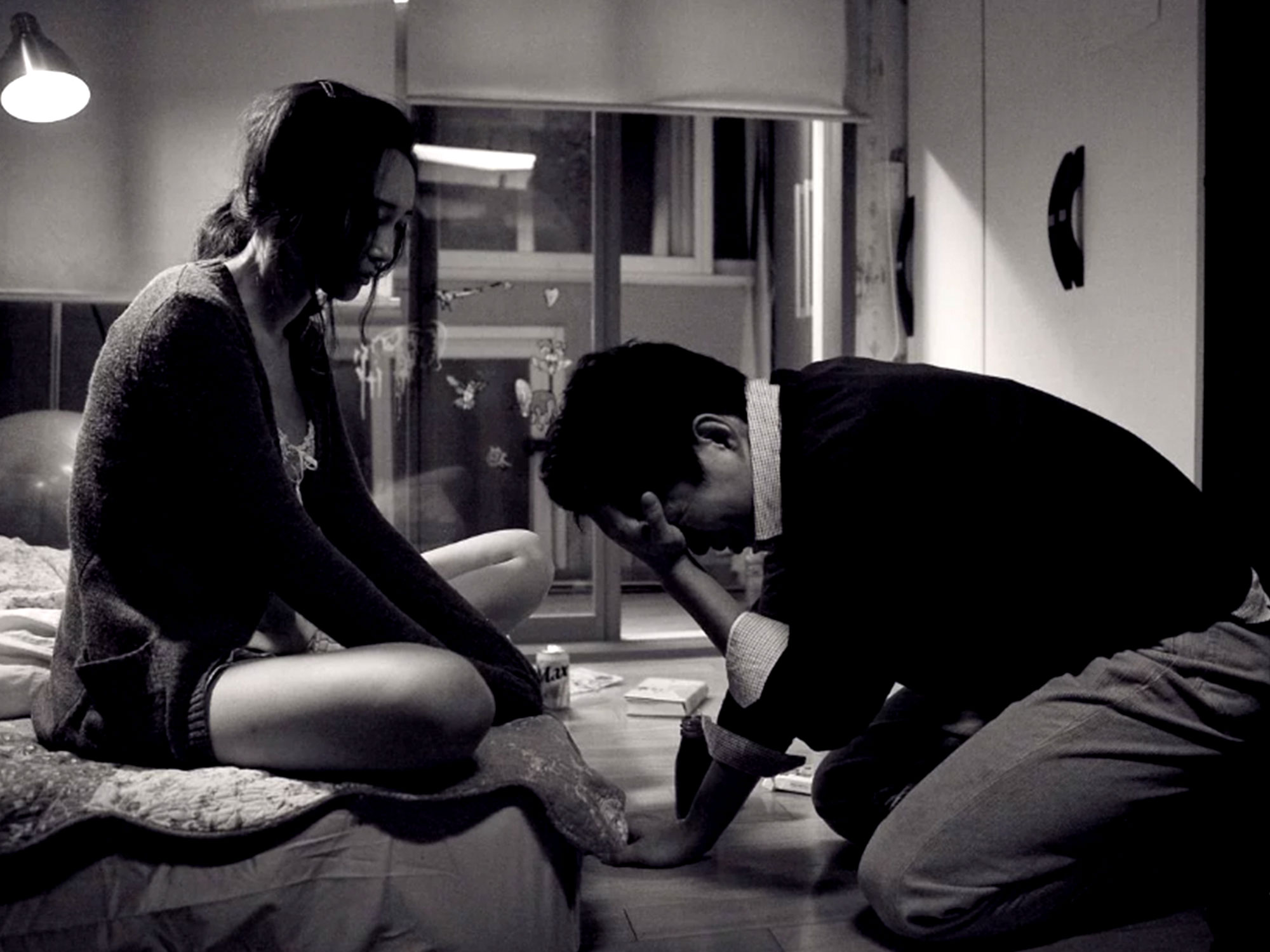

75. The Day He Arrives (Hong Sang-soo, 2011)

Any of the 14 feature films Hong Sang-soo made in the decade could fit here, such is the prolificacy and consistency of the South Korean filmmaker. But this one also serves as an ideal entry point for the unfamiliar – a slippery, snowy, soju-soaked affair in which all his major themes are present. Matthew Lloyd Turner

74. Like Someone in Love (Abbas Kiarostami and Banafsheh Violet Modaressi, 2012)

It’s hard to discard the tragedies when you’re talking about the triumphs, but it’s a bittersweet situation indeed when you’re lauding a film which ended up being a great director’s swan song. This Tokyo-set rondelay follows a young call girl on a whirlwind trip through the city, and constantly, cryptically alludes to the anxieties generated by her unseen personal, family and romantic life. There are no easy answers or dramatic platitudes, which makes it the defining statement from one of modern cinema’s true masters. DJ

73. Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa, 2019)

Time is money in the world of supreme cinephile being Pedro Costa. That is, not just the duration of the shots, but the time taken to fashion films and draw the spiritual essence from actors. Costa’s mode is pure empathy – he makes films as tactile dreams and memories that he can gift to those who don’t tend to have such things. Vitalina Varela is, in many ways, a traditional ghost story about a woman visiting the house of her estranged (and now dead) husband, but looks and feels like nothing else ever made. DJ

72. Personal Shopper (Olivier Assayas, 2016)

Hilma af Klint, a proto-modernist painter whose paintings were inspired by seances, prefaces the mystical ghost work of Personal Shopper. Like Klint, Maureen (Stewart), has a connection to the spirit world. Her brother had just died and between jobs as a personal shopper, she begins to receive mysterious and ghostly text-messages from the beyond. Justine Smith

71. Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Rian Johnson, 2017)

Despite the campaign of hate waged by a very vocal minority of online fans, Rian Johnson’s instalment in the Star Wars saga feels destined to be remembered for all the right reasons. Visually bold, narratively daring, he took a franchise property and made it his own. He took the galaxy far, far away to destinations unchartered and created some truly beautiful set pieces, resulting in that rarest of beasts: a blockbuster with heart and soul. HW

70. The Assassin (Hou Hsiao-Hsien, 2015)

Qiu Shu stars as the “matchless” killer in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s brilliantly fractured wuxia prism that embraces mood and texture over narrative. Despite the film’s period ninth-century setting, each of her lethal movements and vengeful actions can be seen as an act of rebellion in favour of Taiwanese independence from Chinese aggression. GHJ

69. Knight of Cups (Terrence Malick, 2015)

The extraordinary quartet that followed The Tree of Life – of which Knight of Cups proved the pinnacle – was a monumental run for the newly prolific Terrence Malick, one that saw him expand the reach of his formal and poetic principles in a manner largely unseen within mainstream cinematic culture. No one could’ve guessed we’d get six Malick pictures in the 2010s. The decade was all the better for it, and so was the seventh art. Matt Thrift

68. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019)

Through the travails of a fading B-movie star (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his stunt double/gofer (Brad Pitt), Quentin Tarantino pays homage to the ’60s Tinseltown of his boyhood fantasies. In the margins, the Manson family glower and Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) goes about her day, while in the foreground, an industry and a country evolve out of nostalgia. CB

67. No Home Movie (Chantal Akerman, 2015)

Death hangs heavy over No Home Movie, not just in its documentation of the final months of its ostensible protagonist, but in the knowledge that it would be the final work by the great Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman, who took her own life in the year of its release. A companion piece to her 1977 film Letters from Home, which similarly constructed a dialogue between Akerman and her mother, No Home Movie remains prickly and combative to the last, as it prods at historic tensions and the mother-daughter bond. MT

66. Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012)

Taken from the true story of CIA operatives’ years-long hunt for Osama bin Laden, Bigelow’s film captures the moral complexity of the American war machine and its enormity of its involvement across the middle east. Following Jessica Chastain as a canny CIA op, the film queries the role of torture and bribery in bringing terrorists to justice. Christina Newland

65. Meek’s Cutoff (Kelly Reichardt, 2010)

Those who want to be leaders do so because it makes fucking up permissible. It’s lofty status which doubles as an in-built excuse. Stephen Meek is one such leader/fuck-up, heading up a wagon train across the treacherous Oregon territory in Kelly Reichardt’s nail-biting existential trail western. The film, set in 1845, is told from the perspective of the mousey womenfolk whose lives are placed in the hands of reckless male bravado and bullishness. Good luck with that… DJ

64. The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013)

A litmus test for an audience’s willingness or ability to read a text, it seems viewers are still struggling to decide whether Martin Scorsese’s epic stands as a damning indictment of the worst impulses of late-stage capitalism or simply an epic vaudeville, a Rake’s Progress for the ladz. It’s easy to see why some were turned off by the bait and switch of Scorsese’s honeytrap, just as others appeared content to be seduced by Leo’s carnivalesque rogue. Either way, few films digested the worst impulses of the previous decade with such wickedly satirical zeal. MT

63. The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2014)

Wes Anderson has had a fairly busy decade, and his 2014 caper ranks among his very best work. Ralph Fiennes plays the irrepressible Gustav H, the meticulous concierge who takes Tony Revolori’s lobby boy under his wing. Anderson is on usual whimsical form, but against a backdrop of civil war, his baby pinks and plummy purples stand out even more. It’s a melancholy film about found and lost families, as sad and thoughtful as it is fastidious and detailed. HW

62. OJ: Made in America (Ezra Edelman, 2016)

Simultaneously fleet-footed and monolithic, Ezra Edelman’s documentary investigates the OJ Simpson saga, peeling the layers from this giant, rotten cultural onion with forensic precision and intellectual rigour. In this absorbing study of race, class, sport, politics and the media through the prism of one deeply troubled man, Edelman crafts the ultimate rarity: a 467-minute film that could stand to be even longer. AC

61. This Is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi, 2011)

Placed under house arrest and banned from making films by the Iranian government in 2010, Jafar Panahi’s creative future was very much in doubt at the beginning of the decade. But this joyfully experimental, endlessly nimble doc/fiction hybrid co-directed by Mojtaba Mirtahmasb and set in Panahi’s owns apartment/prison eased those fears substantially. It also ushered in a new era of personal and political expression for one of the great living film artists. GHJ

60. The Duke of Burgundy (Peter Strickland, 2014)

If the title sequence and meticulous design elements suggest a patina of ’70s Euro horror, The Duke of Burgundy is far too singular a concoction to write off as an exercise in pastiche. Pinteresque, sapphic role play figures early, before entomological motifs emerge to enrich Strickland’s provocatively sensual bitches brew. As ever with our foremost proponent of sensorial gothic, the first act is but a tease for the audiovisual phantasmagoria unleashed come the third. MT

59. Weekend (Andrew Haigh, 2011)

In Andrew Haigh’s tender, exposed debut feature, a one-night stand between two men quickly becomes not only a more intimate experience, but an opportunity for the two to confront what it means to be a (white) gay man in the modern, western world. Weekend is as intoxicatingly splendid as it is righteously political. Kyle Turner

58. The Wind Rises (Hayao Miyazaki, 2013)

You’ll struggle to find anyone who opposed Hayao Miyazaki’s decision to come out of retirement in 2017. And yet… were it not for the presence of a new project from Studio Ghibli’s silver-bearded maestro on the horizon, The Wind Rises would surely go down as one of the all-time great cinematic swansongs. Miyazaki’s forthcoming How Do You Live? may well prove to be an instant classic, but he’ll be hard pushed to top this soaring semi-autobiographical adventure. AW

57. Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, 2016)

Through its non-linear alien invasion plot line and lush visuals, Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival is a sci-fi film that acknowledges the connection between life’s great joy and unfathomable pain through linguist Louise Banks (Amy Adams), the death of her teenage daughter, and the mysterious extraterrestrial visitors Banks and her colleagues have been charged to study. At a time when the future seemed – and still seems – frightening, Arrival came as a hopeful vision of life and death that sees intense emotion as vital to the human experience. Madeleine Seidel

56. Raw (Julia Ducournau, 2016)

Away from home and deep into the humiliations and discoveries of veterinary school, Justine becomes famished. For the first time, she begins to eat raw meat and a new world of possibilities opens up. A truly corporeal coming of age with a perverse take on what it means to inhabit a human body, Raw is a film of rare pleasures and unexpected surprises. JS

55. Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2014)

Paul Thomas Anderson is one of those infuriatingly great filmmakers who is yet to make a bad film (and long may his reign continue). His sun-drenched Californian crime caper, starring Joaquin Phoenix, is one of his knottiest works – no surprise, since it’s adapted from a Thomas Pynchon novel – but that only makes it more rewarding. Confounding, challenging and often very funny, and it’s great to see Phoenix loosen up and have some real fun. HW

54. American Honey (Andrea Arnold, 2016)

Andrea Arnold’s penchant for street casting brings a joyous naturalism to her first non-British film. Spotted by Arnold while sunbathing on a Florida beach, Sasha Lane gives an immense performance as Star, the Oklahoma teen who flees her family for a life on the road selling magazine subscriptions with Shia LaBeouf. Well, someone’s got to. TH

53. Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel, 2012)

With backing from Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, co-directors Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel plunged audiences into the murky, eerily sensuous world of deep-sea fishing. Their hard-won footage offers a novel take on the experimental documentary, privileging texture and sensation over arc-based narratives or, in its most ravishing moments, basic coherence. CB

52. Paterson (Jim Jarmusch, 2016)

Adam Driver delivers his finest performance as a bus driver with the soul of a poet, moving through his quotidian routine with grace and an appreciation for the little things. Jim Jarmusch’s gentlest film uses visual rhyme and high-minded allusion to show how this man – a working artist – reconciles the demands of everyday life with his need to create. CB

51. 20th Century Women (Mike Mills, 2016)

In this hazily kaleidoscope coming-of-age film, Mike Mills was inspired by his own childhood to tell a story of women raising a boy at the end of the 1970s. Annette Bening created one of the decade’s best screen characters in wisecracking Dorothea, a woman born during the Depression but embracing the era of punk. Pamela Hutchinson

50. Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley, 2012)

Sarah Polley’s deeply personal debut documentary is a self-aware, sensational use of storytelling that navigates through her family’s elusive past with a skill that belies her early status in non-fiction. The less said of Polley’s heritage the better; this is the kind of cinematic experience that benefits from going in blind. BW

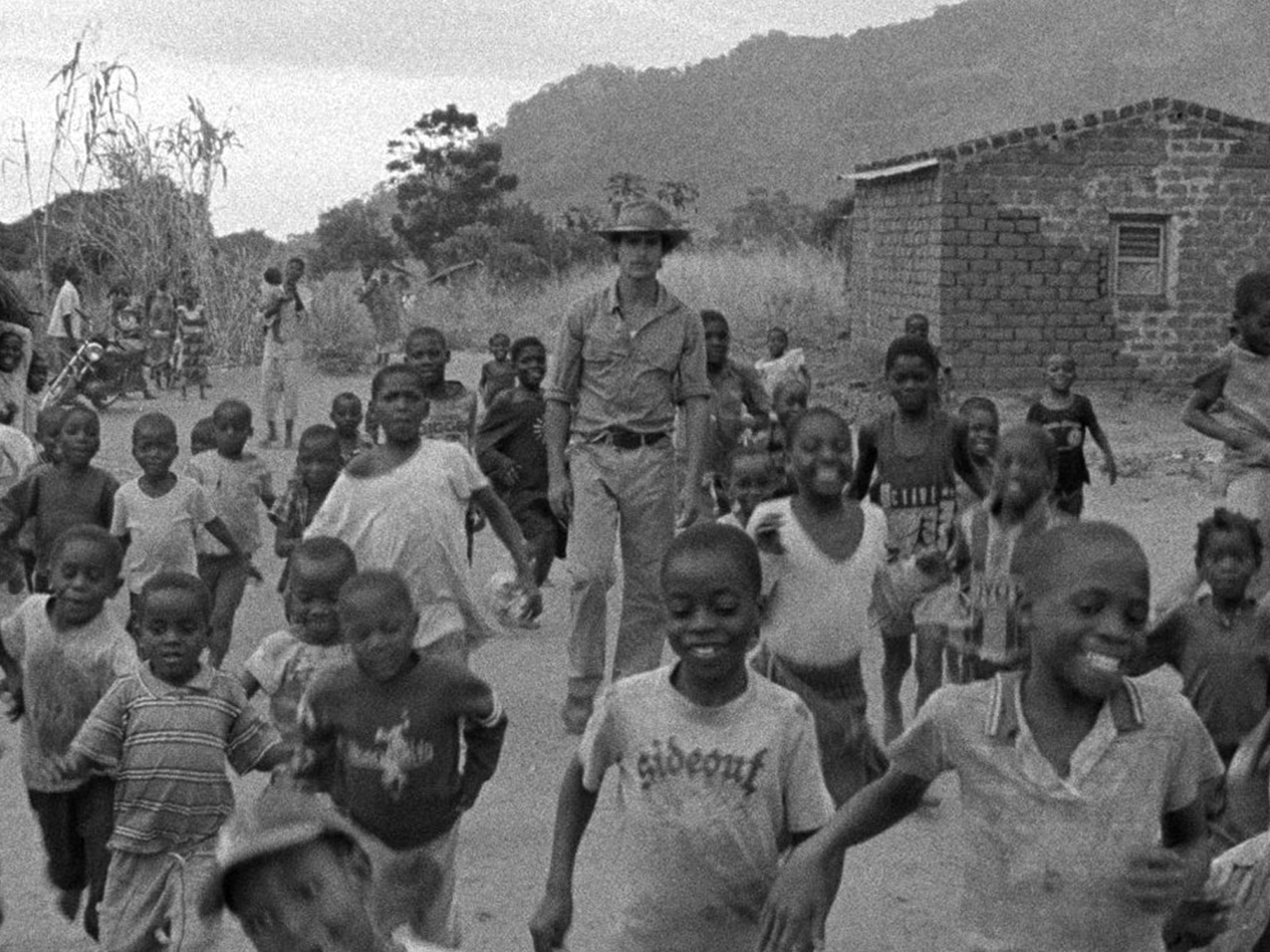

49. Cameraperson (Kirsten Johnson, 2016)

Ingeniously, in Cameraperson director Kirsten Johnson used fragments from the films she shot over the course of 25 years working as a cinematographer to craft a narrative about her own life. It’s a riveting, and wholly original film that locates the soul of its subjects through the camera’s discerning, sympathetic gaze. PH

48. The Other Side of the Wind (Orson Welles, 2018)

People love to read about the movies that never came to be – the broken dreams of deceased auteurs that didn’t, for whatever reason, see the light of day. In the case of Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, streaming giants Netflix decided to parlay their considerable financial resources into dredging this dream up from the doldrums and giving it the life it never got back in early 1970s. Having the chance to bask in the sensory overload of a work the director himself described as “a new kind of cinema” allows us to see just how much Welles remained one of the great innovators of the medium until his dying day. DJ

47. Call Me by Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017)

The film that launched a thousand stan accounts, Luca Guadagnino’s tender coming-of-age romance set in the dreamy idyll of Northern Italy made an instant star of Timothée Chalamet. Elevated by lush, hazy cinematography, Sufjan Stevens’ beautiful score and Michael Stuhlbarg’s showstopping supporting performance, Call Me by Your Name marked a watershed moment for queer cinema; tender and cheeky and heartbreaking in equal measure. HW

46. L for Leisure (Whitney Horn and Lev Kalman, 2014)

The F for Fake of grad school movies, Whitney Horn and Lev Kalman’s super lo-fi early ’90s-set curio follows a group of students as they embark on various trips over the course of a single academic year. Constructed as a series of meandering, ostensibly unconnected vignettes in which each “character” is given ample opportunity to shoot the shit, L for Leisure might just be the most elaborate cinematic in-joke ever pulled. AW

45. Hereditary (Ari Aster, 2018)

In this 2018 horror hit, anxieties about family and grief turn demonic in the hands of director Ari Aster and lead actress Toni Collette. Annie Graham (Collette) is grappling with her complicated feelings surrounding the death of her mother, setting off a traumatic series of events that lead the Grahams to uncover terrifying secrets about their late matriarch. Bridging the gap between traditional and experimental, slow-burning horror, Hereditary is brutal and beautifully crafted in equal measure. MS

44. Elle (Paul Verhoeven, 2016)

The French philosopher Blaise Pascal famously remarked that if Cleopatra’s nose had been shorter, the whole face of the world would have been changed. Something similar can be said of Isabelle Huppert’s eyebrows in Elle: with every knowing elevation and quizzical flicker, she telegraphs worlds of biting commentary and exquisitely restrained emotion. Catherine Bray

43. Gone Girl (David Fincher, 2014)

David Fincher’s poisonous and pulpy adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s bestselling thriller captures the obsessive and toxic turns of one seemingly strait-laced prototypical heterosexual couple. Full of twists and turns, false leads, fourth-wall breaks, Gone Girl a deeply funny and astute portrait of the expectations and pressures of life under capitalism. JS

42. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010)

Apichatpong Weerasathekul’s audience expanded after this film saw him collect the Palme d’Or in 2010. An otherworldly film about Thai traditions of transformation and reincarnation, Uncle Boonmee follows a man who, facing his final days, starts to find himself surrounded by strange sights and spectral presences. MLT

41. High Life (Claire Denis, 2018)

Claire Denis’ out-of-this-world debut English-language drama saw Robert Pattinson marooned amongst the stars, contemplating fatherhood, forgiveness and the frailness of man. It also brought new meaning to the phrase “in space, no one can hear you scream,” via a solo sex scene in a blacked-out cosmic container called “the fuckbox” that’s among the decade’s most unnerving. Al Horner

40. Zama (Lucrecia Martel, 2017)

It was a long wait for Argentinean director Lucrecia Martel’s fourth feature, but boy was it worth it. This reverent adaptation of Antonio di Benedetto’s 1956 novel follows a bureaucrat stationed in a remote Paraguayan encampment who just can’t seem to do anything that makes him or those around him happy. It’s a quasi-psychedelic character portrait which begins like a corporate comedy caper (with scene-stealing llamas) and climaxes as a wistful and violent western. DJ

39. 120 Beats Per Minute (Robin Campillo, 2017)

In fraught queer landscape of the early ’90s amid the AIDS crisis, fluidity is not only important, it’s what gives queers a sense of solidarity. Thrusting the audience in the middle of ACT UP Paris meetings, actions, and dance parties, Director Robin Campillo humanely observes the way that community, politics, pain and pleasure are inextricable from one another. KT

38. Leviathan (Andrey Zvyagintsev, 2014)

“Shall not one be cast down even at the sight of him?” The Bible basically nails it: Leviathan is a hefty beast and a crushingly depressing watch, but in a good way – Andrey Zvyagintsev constructs a rich and inexorable study of low-level corruption in modern Russia, as clear-eyed as it is cunning. Catherine Bray

37. Burning (Lee Chang-dong, 2018)

After a long hiatus, Lee Chang-dong followed up Poetry’s quietly angry critique of patriarchal privilege with the magnificent and beguiling Burning. A treatise on consumerism, masculine rage and class-based discontent, the film immerses us in the protagonists subjective POV, his unravelling portrayed with a fascinating, enticing ambiguity. Kambole Campbell

36. The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky, 2011)

Despite a 2017 short and a site-specific installation piece this year, the Hungarian slow cinema maestro appears to be sticking to his guns in describing The Turin Horse as his final cinematic statement. Eschewing the ironic absurdism of previous features for a po-faced examination of futility and stasis, it’s a study in survivalism and human nature that serves as a clear-eyed summation of a nine feature formal project. A rapturous final statement from one of cinema’s titans. MT

35. Magic Mike XXL (Gregory Jacobs, 2015)

There are some cinematic images that stay with you. Joe Manganiello gyrating as he pours a bottle of water down himself to the beat of Backstreet Boys’ ‘I Want It That Way’ is one of them. In this sequel to Steven Soderbergh’s melancholy mediation on toxic masculinity and the body as commodity, his long-time colleague Gregory Jacobs stepped up to direct. Magic Mike XXL does exactly what it says on the tin. Impossibly attractive and charming scantily-clad men bust out song and dance routines while a host of beautiful, powerful, low-key terrifying women run the show. HW

34. Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Céline Sciamma, 2019)

Even for a director who trades in minimalism, there is a surprising slowness to Céline Sciamma’s fourth feature. Upon first watch, the film is a slowly burning seduction, quietly hypnotic until a climax at the end of the second act. But both the silence and noise linger long after, even on first blush, frames and dialogue uniquely burnt into memory. “Not everything is fleeting. Some feelings are deep,” Adèle Haenel’s Heloise says. Ella Donald

33. Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, 2019)

Bong Joon-ho has always been a master of tonal whiplash, moving from dark drama to absurdist comedy with relish. He outdid himself with the Palme d’Or-winning Parasite, which somehow mutates from a hilarious family farce into the decade’s most searing social satire: a condemnation of late capitalism that stays with you for weeks after. AH

32. The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, 2012)

The gravity of these images makes you feel like you’re sinking through the floor as former-death-squad leader Anwar, now an amiable grandfather, instructs Joshua Oppenheimer as the documentarian re-stages gruesome murders from the Indonesian genocide of 1965-66. The blood of innocents runs through this hugely empathetic film, along with an urge to understand how killers account for their evil, state-sanctioned deeds. SMK

31. Holy Motors (Leos Carax, 2012)

As Denis Lavant rides around in a limousine, inserting himself in a series of odd scenarios, filmmaker and certifiable madman Leos Carax explodes the notion of “the actor” with these inscrutable performances. Suffused with the sheer possibility of the cinematic form, prone to flights of fancy involving accordion marching bands and lecherous trolls, there’s truly nothing else like it. CB

30. Phoenix (Christian Petzold, 2014)

Christian Petzold makes films which seem to exist out of time. Phoenix, the German writer/director’s intimate, atmospheric portrait of a disfigured Holocaust survivor who sets out to discover the truth about the man she loves, manages to be at once unambiguous in its setting – postwar Berlin – and refreshingly unconstrained by the specific style and mood of the period. The last scene is an absolute dream. AW

29. Poetry (Lee Chang-dong, 2010)

Lee Chang-Dong’s masterful Poetry proceeds with a premise from heaven: a Korean grandmother Mija (the brilliant Yoon Jeong-hee) confronts the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease while simultaneously dealing with the fallout from a terrible crime in which her teenage grandson (Lee David, playing one of cinema’s all-time great little shits) may have been a key player. It’s impossible to know where this crushingly sad yet breathtakingly beautiful film is headed from one moment to the next. AC

28. First Reformed (Paul Schrader, 2017)

The world is going to end in a future within sight, and nobody’s doing anything about it. This terror animates Paul Schrader’s portrait of a country priest (Ethan Hawke) turning to a Christian jihad in a last-ditch effort to salvage what’s left of God’s creation. His one-man holy war mounts a persuasive argument for righteous extremism in the end times. CB

27. Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010)

Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hardy, Ellen Page and others found themselves disappearing down rabbit holes of their own making in this dazzling ‘mind-heist’ sci-fi in which data thieves could enter the dreams, and dreams-within-dreams, of their marks. Full of the brazenly overcomplicated bombast that Christopher Nolan accomplishes with such gusto, this was not only a high watermark of original, intelligent blockbuster filmmaking, but after a decade in which franchise films dominated the box office to an unprecedented degree, it in retrospect looks like a swansong to a bygone studio mode. IM

26. The Irishman (Martin Scorsese, 2019)

Reuniting Scorsese’s old collaborators De Niro, Pesci and Keitel – plus throwing Al Pacino into the mix – this chilly, gradually-paced epic spans the life and career of mob hitman Frank Sheeran across the American mid-century. Elegiac, discomfiting, and surprisingly funny, The Irishman is a late-career masterpiece from one of American cinema’s remaining heroes. CN

25. Boyhood (Richard Linklater, 2014)

Boyhood was one of those films where an artist wheels comes from out of nowhere and presents ‘just a thing I’ve been tinkering with,’ and it turns out to be their defining achievement of their feted career. Martin Scorsese had de-ageing technology by the shedload for The Irishman, but Richard Linklater went one further and captured the annual trials and tribulations of Mason (Ellar Coltrane) across 12 painstaking years. How this logistical nightmare manages to all come together into one of the most poetic and profound statements on how we naturally adapt to the people and places around us, we’ll never know. DJ

24. Paddington 2 (Paul King, 2017)

The rare sequel that surpasses its predecessor, the script by Paul King and Simon Farnaby is sharper, the story is sweeter (without turning saccharine), and Hugh Grant’s villainous Phoenix Buchanan should have earned an Oscar nomination. A much-needed slice of joy, the marmalade-sandwich loving bear is a strong advocate for the power community spirit. EF

23. Certified Copy (Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

A man and a woman drive through the countryside, exchanging thoughts on art and authenticity. We may recognise them as Juliette Binoche and William Shimell (the latter in his screen debut), but their true nature – as possible amants, as ideological opposites – remains an enigma through Abbas Kiarostami’s ceaselessly brilliant late-career thought exercise. CB

22. Song to Song (Terrence Malick, 2017)

Terrence Malick released more films this decade than he during the previous three decades combined. While all six could be described as major, this swooning, spinning, swinging tale about two struggling musicians (Ryan Gosling and Rooney Mara) who fall in and out and in love is arguably the most emotionally stunning. Set against the raucous music scene in Austin, the film’s heightened, ultimately hopeful melodrama punctures the conformity of modern social interaction that often sucks up all the air in a burgeoning romance. GHJ

21. Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach, 2012)

Daring to dream big doesn’t always lead to the life you want, rather this coming-of-age story deals with the realities of a stalled career, shifting friendship priorities, and maintaining a sense of hope when everything goes wrong. Featuring an incandescent lead performance by co-writer Greta Gerwig, dancing through New York City to David Bowie has never looked better. EF

20. The Souvenir (Joanna Hogg, 2019)

“You’re lost and you’ll always be lost,” Julie’s first love Anthony tells her. With this unflinching memoir, Joanna Hogg is found. She traces the contours of a doomed relationship, resurrecting its volatile intimacy in such refined and painful detail that it feels like a living monument to impossible love and a source of wisdom to those still in its grasp. SMK

19. Eden (Mia Hansen-Løve, 2014)

When you’re a kid, your parents constantly hector you with the question: what are you going to do with your life? Mia Hansen-Løve’s fourth feature is about a man (inspired by her own brother Sven) who believes he knows what he wants to do, and dedicates his life to achieving his dream of being a world renowned dance music DJ. Yet what if it becomes clear that you are living an impossible dream, and that to achieve any kind of happiness you need to hit the hard reset. It’s stands as the director’s greatest, most richly philosophical and inspiring film to date. DJ

18. Lady Bird (Greta Gerwig, 2017)

Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut is a generation-defining film. Anchored by an incredible performance from Saoirse Ronan in the titular role, the film follows Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson and her mother (Laurie Metcalf) as they navigate Lady Bird’s senior year of high school and the drama, heartbreak, and rapid change that accompanies it. Lady Bird is a bittersweet tribute to adolescence in the early 2000s, and even though the film is specific to a certain (and yes, rather privileged) experience, Gerwig crafts a narrative so attuned with the ups and downs of growing up that it’s nearly impossible to not see a bit of yourself on screen. MS

17. Stray Dogs (Tsai Ming Liang, 2013)

With Stray Dogs, master Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang pushes his craft to its logical extreme, working with his long-time (and long-suffering) actor collaborator Lee Kang-sheng to make this slow, severe and utterly sublime film – the fitting conclusion to their increasingly desolate series of features exploring alienation, poverty and desire. MLT

16. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, 2018)

Released on Netflix but best appreciated on the sparkling silver screen, Alfonso Cuaron’s gorgeous sideways autobiography centres not on his own childhood memories but on the experience of his indigenous nanny, a holy innocent buffeted by misfortune. The result is a grand celebration of life, family, empathy, integrity, rebellion, food, cinema – all the good stuff. TH

15. You Were Never Really Here (Lynne Ramsay, 2017)

In a more just world, Lynne Ramsay would have been garlanded the world over for her bruising, tightly-coiled 2018 thriller, in which Joaquin Phoenix plays an avenging hitman who becomes embroiled in the dark world of child sex trafficking in New York state. Like her previous films, We Need to Talk About Kevin and Morvern Callar, she adapts from a novel but creates her own distinct vision – a world where softness exists alongside unbearable brutality. HW

14. The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2011)

Terrence Malick hinted at a new form of film syntax with his “comeback” twosome of 1998’s The Thin Red Line and 2005’s The New World, but it wasn’t until 2011’s The Tree of Life where he was able to form fluid, florid sentences. The film juxtaposes the accidental death of a young man against the history of creation and, while tracing the evolution of grief as an emotion that is couched in a feeling of near-sublime exaltation. This really is as grandiloquent, philosophical and rhapsodic as cinema gets. DJ

13. The Social Network (David Fincher, 2010)

The Social Network is a masterclass in biographical filmmaking, thanks in no small part to Aaron Sorkin’s script – sharp enough to draw blood – and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ score, which mixes melancholy piano motifs with glitchy synths. Jesse Eisenberg was robbed of an Oscar for his performance as enfant terrible Mark Zuckerberg, and the film’s lasting prescience as Facebook’s stranglehold on the communications landscape begins to dwindle cannot be forgotten. David Fincher’s film has aged like a fine wine. HW

12. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2012)

Paul Thomas Anderson burrows deep into the id of postwar America with this immaculate period piece, a years-spanning battle of wills between a cult leader (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) and his most devout follower (Joaquin Phoenix). A massive and essential addition to the States’ national cinema canon, it plays out like a dense midcentury novel. CB

11. Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017)

Get Out was a phenomenon full of now-iconic ideas and imagery: Daniel Kaluuya’s horrified face, The Sunken Place, the sound of a spoon scraping around the inside of a teacup. It announced director Jordan Peele as a brilliant Hitchcockian mischief-maker and was the first true film of the Trump era, encapsulating how America’s present is a slave to its racially-fraught past. AH

10. Tabu (Miguel Gomes, 2012)

One of Miguel Gomes’ abiding interests is in the idea of art as a chronicle of a moment in time, be it a painting, a political folk song, or an object that draws your mind back to a happier time. In Tabu, yen for the crisp, unadorned romanticism of silent-era cinema is augmented by a wicked sense of irony and some touches which hark back to a narrator perhaps mixings up times and places in her own head. It’s a magical film about the cinematic nature of memory, and also boasts an extraordinary, improvised piano soundtrack by Lisbon local, Joana Sá. DJ

9. Margaret (Kenneth Lonergan, 2011)

After years of delays, Kenneth Lonergan’s operatic meditation on guilt and coping in New York was restored to its fullest glory and allowed to see the light of day in theatres. Between Lonergan’s tone-perfect direction and Anna Paquin’s thunderstruck performance as a teen learning that she may not know everything after all, the wait was worth it. CB

8. It’s Such a Beautiful Day (Don Hertzfeldt, 2012)

In just 62 minutes, director/producer/writer/animator/narrator Don Hertzfeldt manages to pull off a quite incredible feat: he tells a story, rendered largely with crude stick figures, which runs the full gamut of human experience. Death, life, love, loss, the inevitable death of the cosmos and all within it – all are pontificated upon with Hertzfeldt’s profound, crude, bleak and hopeful masterpiece. HW

7. Toni Erdmann (Maren Ade, 2016)

It’s great when you see a movie that took a little longer to make, and it’s even better when you can actually see that time, patience and the artisan workmanship up there on the screen. The third feature by German maestro Maren Ade, when taken as a glorious whole, feels not like a labour of love – as that would infer that there was an element of romantic, directionless energy employed in its making. No, this is like the screwball comedy equivalent of a gorgeous hand-carved canoe. It is the exemplary saga of an eccentric father who is determined to make his daughter, now a high-rolling businesswoman based in Budapest, remember the joys of her youth. Whatever Ade does next, the world will be watching. DJ

6. Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015)

It would be easy to overhype Todd Haynes’ landmark 2015 film, one that has thousands of praising words and a still-ardent fandom that continues to grow even years after its release. Lovingly and passionately constructed by all involved over its long production period, it’s a film that’s easy to adore. But moreover, Carol represents a viewing experience that encapsulates why we go to the movies: escapism, community, the chance to feel understood. Undoubtedly, it will be remembered in decades fo come. ED

5. Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller, 2015)

So purely chaotic and elemental that it feels like it was forged in the fires of hell, Mad Max: Fury Road is George Miller’s magnum opus. Punctuated with some of the most dynamic action scenes ever filmed, it’s perfectly orchestrated anarchy from beginning to end; its post-apocalypse realised in vivd colour and tempered by palpable emotional stakes. KC

4. Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017)

Paul Thomas Anderson’s ravishing eighth feature marked a significant departure from his previous work; in style and setting if not theme or tone. A spry, acerbically funny deconstruction of masculinity set in 1950s London, it sees Daniel Day-Lewis on sensational form as fashion designer Reynolds Woodcock, whose fastidious life comes unstitched when he meets the one woman he’s unable to mould to his will (Vicky Krieps). PTA’s portrait of the artist as a hungry boy may foreground the director’s preoccupation with unchecked male ego, but it’s really all about Alma. AW

3. Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2013)

The Coen brothers’ week-in-the-life portrait of a struggling folk singer is their most melancholy film to date, eloquently articulating the heartbreak of watching your life slowly fall apart. Oscar Isaac is utterly magnetic as the frustrating, charming, hopeless Llewyn Davis, cast adrift under the blue-grey winter light of an unsympathetic New York City that offers no respite for the weary. Funny, bleak, and achingly beautiful with a soundtrack that stands up as one of the decade’s greatest, it’s a perfect film about dreams, missed opportunities, and the perils of the gig economy. HW

2. Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016)

The poetic, emotive beauty of Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight is striking enough to feel like an artistic statement of intent. Jenkins uses a triptych structure and a trio of actors to tell the elliptical story of Chiron, a boy who struggles to come to terms with being gay in his working-class black community. It’s a haunting, luminous film that’s difficult to forget once seen. CN

1. Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

An extraterrestrial falls to Earth and snatches the body of Scarlett Johansson, cuing up an interrogation of what it means to be mortal that convincingly inhabits a space outside the human. Jonathan Glazer’s images of abstraction and Mica Levi’s string-section-from-hell provide a beautiful, haunting reminder that the root of “alienation” is “alien.” The ideal combination of the cerebral and the emotional, with an aesthetic halfway between a chilly minimalism and a surrealist lushness, Under the Skin is an expert feat of artistic calibration – and despite all the free-floating dread, it’s also one of the most improbably sexy movies of the decade. In its most affecting moments, Glazer’s attempt to locate the meaning of life (in both the biological and philosophical senses) seems to contain within it all of creation. CB

The post The 100 best films of the decade: 2010-2019 appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments