Criterion‘s collection of Showa-era Godzilla films is a cinematic feast

In 1954 the Japanese crew of the Lucky Dragon No 5 fishing boat were caught in the miscalculated vicinity of Castle Bravo, a hydrogen bomb test conducted by the US at Bikini Atoll. The incident compounded the national trauma caused by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, causing the death of one crew member and generating concern that Japan’s fishing industry was contaminated.

Responding to the fears felt across Japan, Ishirō Honda’s 1954 film Godzilla introduced the titular kaiju as a consequence of mankind’s experiments with thermonuclear weapons. Thanks to compassionate storytelling and ground-breaking special effects, Godzilla became a pop culture icon, going on to appear in over 35 feature film and various other media.

Across 15 films in studio Toho’s ‘Showa-era’, Godzilla came to embody the roles of antagonist, anti-hero and anthropomorphic superhero. Given the historically arduous process of officially obtaining many of these films in the UK, the emergence of the Criterion Collection’s Godzilla: The Showa-era Films 1954-1975 feels long overdue. Covering two decades’ worth of films, the boxset reveals not only how the studio developed game-changing practical effects, but how they consistently refined their techniques in accordance with changing audience interests, concerns and trends. Most pertinently, these films still chime with contemporary concerns, exemplifying the allegorical power of monster movies.

For example, the appearance of Mothra provides a powerful lesson in the exploitation of indigenous communities. When the moth-like kaiju’s egg washes ashore in Japan and is swiftly sold to businessmen as a tourist attraction in 1964’s Mothra vs Godzilla, its Shobijin fairies are unable to negotiate its return, and while Mothra sleeps in 1966’s Ebirah, Horror of the Deep, its Infant Island inhabitants are kidnapped by an evil corporation who exploit their native resources to fend off the film’s crustacean villain.

The franchise regularly muses on the Space Race of the ’60s in the likes of Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster from 1964 and Invasion of the Astro-Monster from 1965, incorporating astronauts, space monsters and alien saboteurs while Godzilla is repositioned as an anti-hero. In 1968’s Destroy All Monsters, a group of astronauts become the central enablers of victory when aliens seize control of Earth’s domesticated kaiju.

Unpredictable weather conditions backdrop 1967’s surprisingly lacklustre Son of Godzilla, introducing climate change concerns that would later define the formidable foe in 1971’s Godzilla vs Hedorah: an alien lifeform multiplied by the world’s industrial waste. Featuring some of the scariest imagery in the series – a fish tank engulfed by sludge, a child drowning in industrial waste, people dissolving – Godzilla vs Hedorah is one of the more divisive films in the series, perhaps due to its inclusion of psychedelic rock interludes and infographic-like animations aimed at children. Yet it is one of the most timely entries, perfectly balancing its adult and adolescent protagonists.

Before that, 1969’s All Monsters Attack adapts pre-existent footage from Son of Godzilla into a narrative about Ichiro, a child who spends his time scavenging through dilapidated buildings and dreaming of a friendship with Godzilla’s son Minilla. A played-down entry in the franchise, it’s one of several exploring how children might respond to a world inhabited by monsters, including 1973’s Godzilla vs Megalon, which captures the popularity of robots amid youngsters at the time and introduces the sentient cyborg Jet Jaguar who teams up with Godzilla to fight Megalon and the previous film’s antagonist, Gigan.

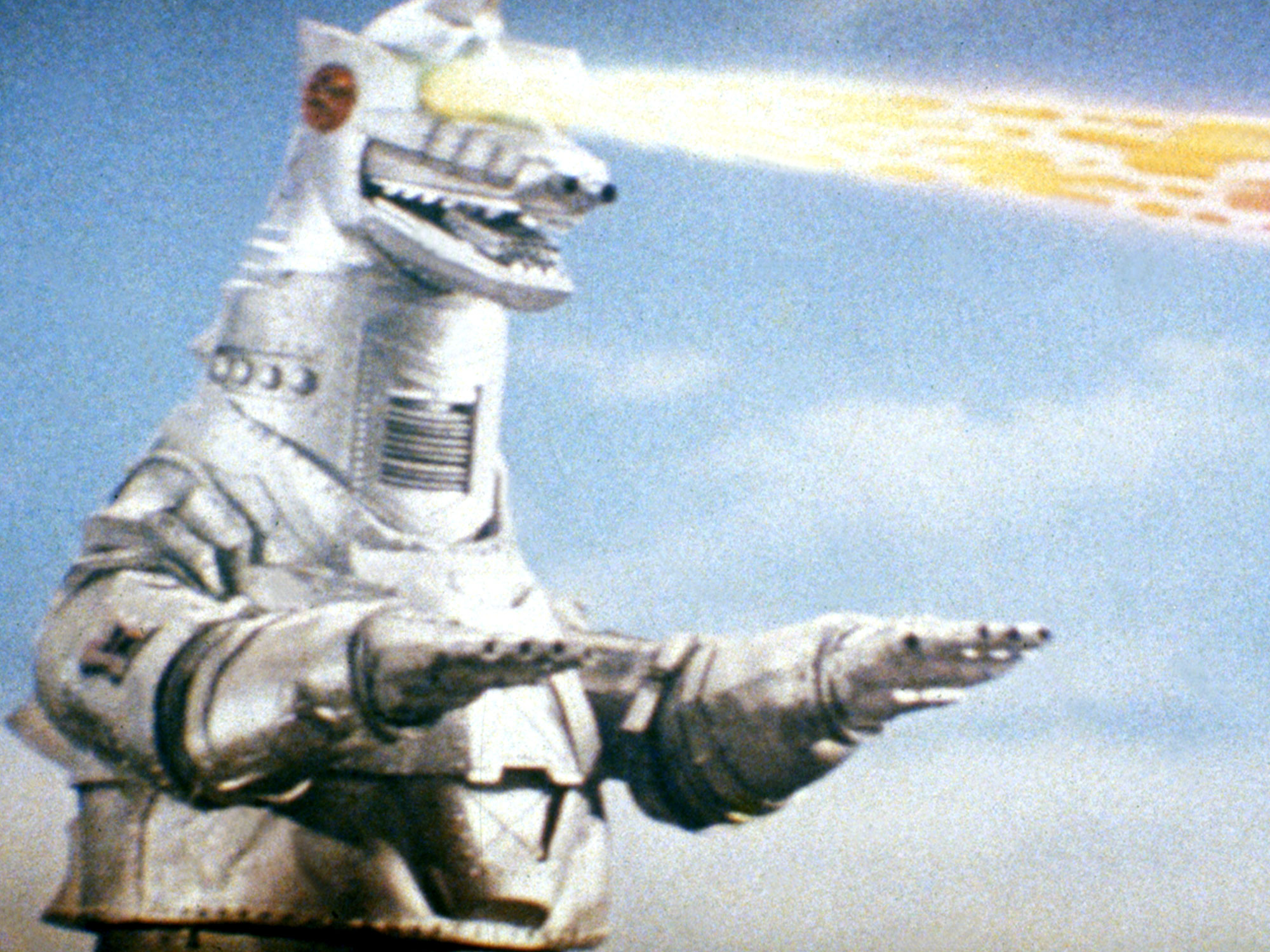

Guiding the series back into darker territory, and likely to resonate with those dismayed by today’s post-truth politics, 1974’s Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla introduces the mechanised doppelgänger of Godzilla, who attempts to dismantle the public image of the reformed kaiju. Honda returned to direct its follow-up, Terror of Mechagodzilla, the next year, closing out the Showa-era with a tragic romance-injected plot that best demonstrates the identifiable role that humans play in so many of the Godzilla narratives. It’s a component of the series that is constantly adapted, giving us a varied line-up of scientists, reporters, romantics, misfits, anti-heroes and children as moral compasses.

Variance and refinement are precisely what define these Godzilla films. The special effects work really hits its stride around Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster before stepping into pyromaniacal territory with Godzilla vs Gigan. The supplementary 1986 documentary Toho Unused Special Effects Complete Collection is a must-watch, highlighting the unfortunate relegation of other kaiju at the hands of the inherited Westernised, Godzilla-centric predication of Toho’s output.

Much of the all-star team seen in Destroy All Monsters appeared in absentia in Toho films first, which will likely be a sore point for those who have their personal favourites from the 11-fold gang which contributes to one of the best brawls in the collection, or those simply wishing to see the special effects in the studio’s kaiju films develop across one chronological sitting.

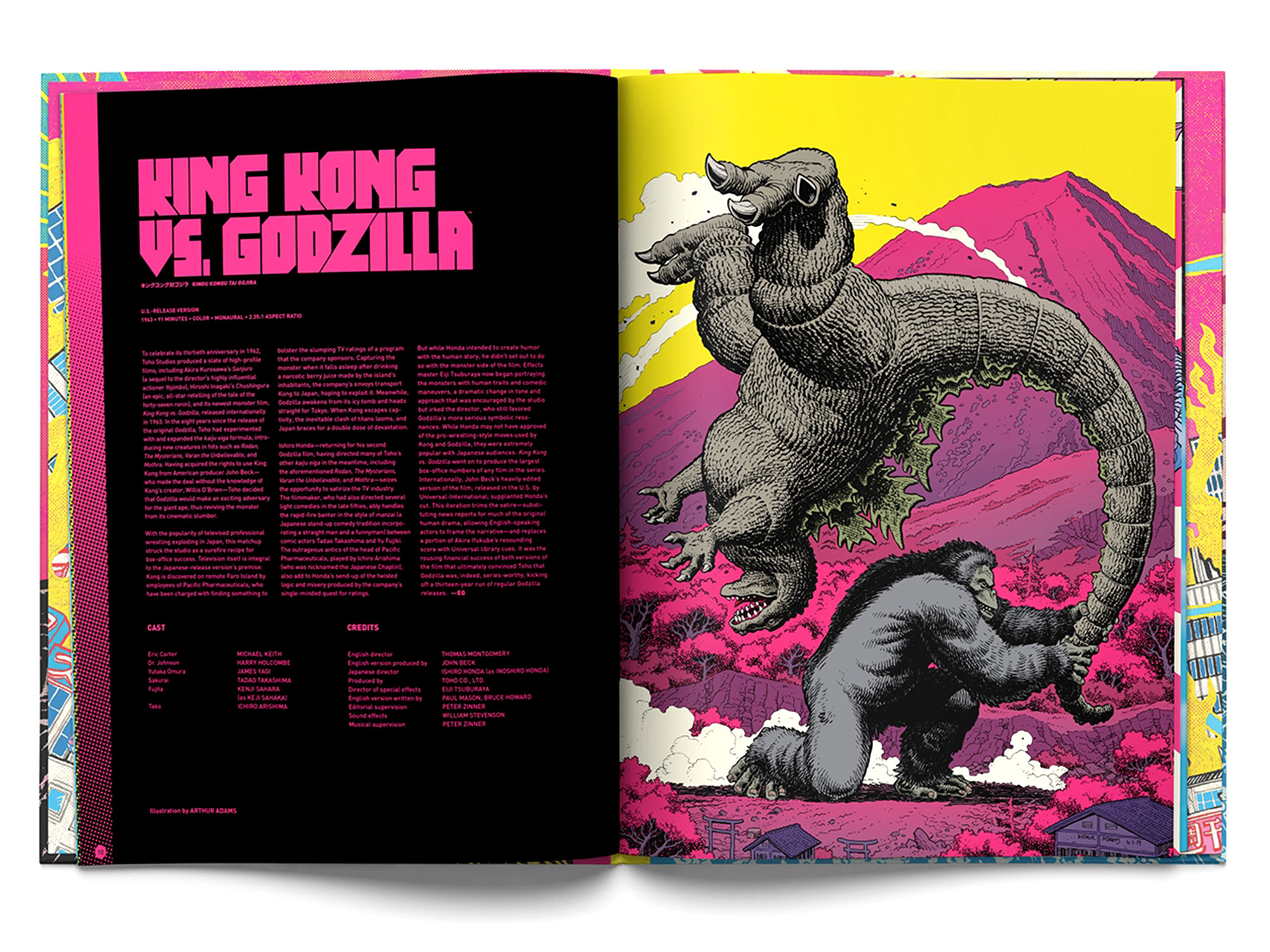

That said, this collection is a wholesome and varied cinematic feast. Comprised of essays on each film and newly commissioned illustrations, the boxset comes in an appropriately large book format capable of devastating the order of any OCD-ridden collector’s shelves, much like Godzilla’s occasionally forgivable clumsiness. Here’s hoping this release sparks wider interest in Toho productions; as with many of the subsequent and adjacent kaiju films, the studio’s war films and Honda’s earlier works are equally deserving of attention.

The post Criterion‘s collection of Showa-era Godzilla films is a cinematic feast appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments