Glancing back over the incredible career of British documentarian Kim Longinotto, one might generalise that she has, through her films, shown an abiding interest in the female victims of male violence. As far back as her meticulous and patient 1998 film Divorce Iranian Style, and through work such as 2005’s Sisters in Law, 2008’s Rough Aunties, 2010’s Pink Saris and 2015’s Dreamcatcher she has focused on oppressed women who have chosen to fight their corner.

At first, her new feature Shooting the Mafia seems like something a bit different for a director who usually prefers a confessional, journalistic and observational mode. This time around we have reams of juicy archive footage, monochrome photography slathered in that Ken Burns-style slow directional zoom, and only a small amount of new material.

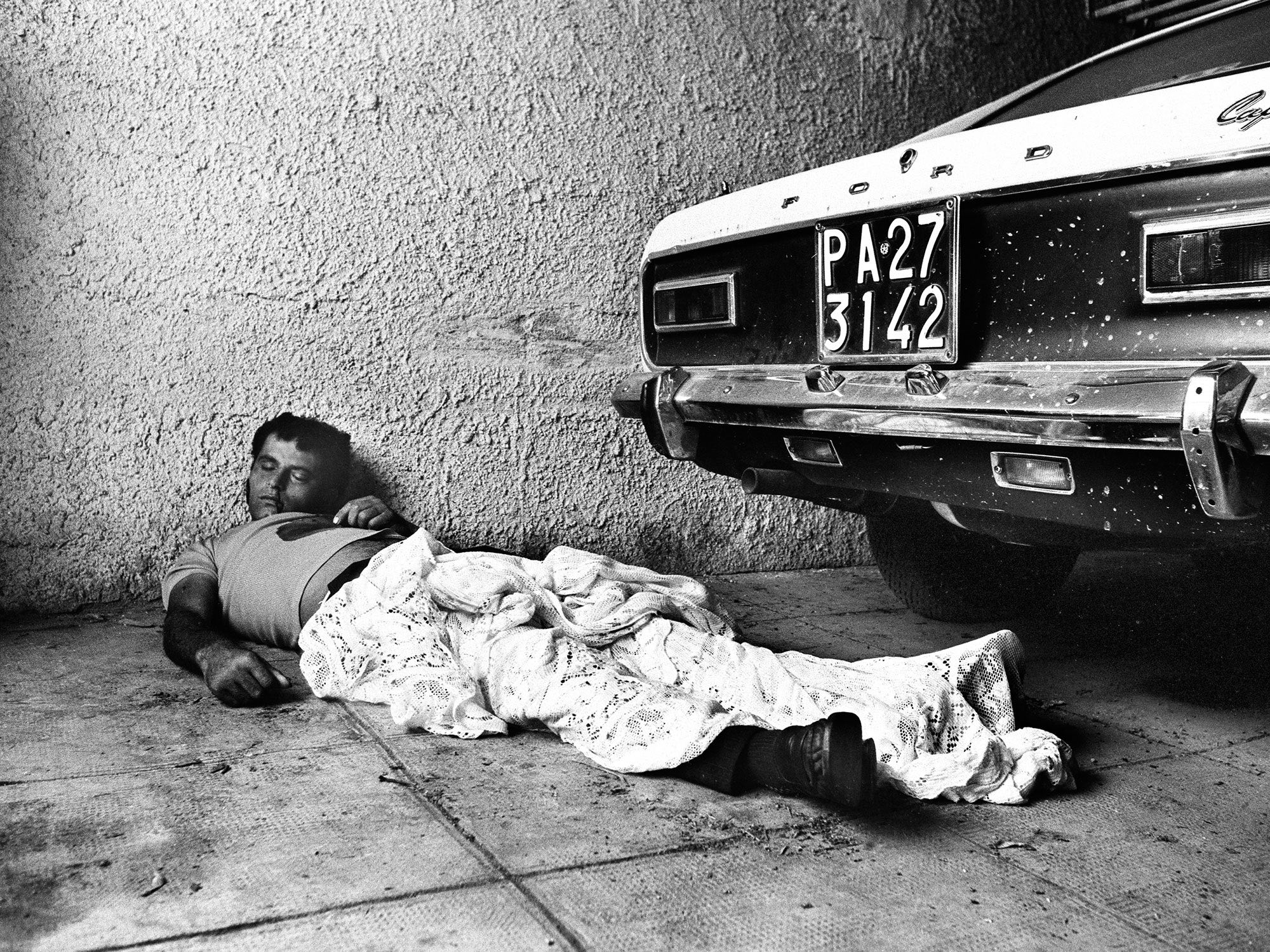

This is a profile of Letizia Battaglia, a Sicilian photojournalist who worked throughout the ’70s and ’80s for the (now defunct) left wing newspaper L’Ora. Her grisly beat saw her first on the scene for the various and frequent Mafia slayings in and around the city of Palermo, and one recurring visual motif of her photographs is a corpse lying beneath a bloodied white clothe with blood flowing out in all directions.

While her vocation meant she had to witness macabre scenes often shielded from public view, an ulterior motive soon comes to light. She started to document the grief of family members (often mothers) upon learning that their son had, say, been clipped in broad daylight for missing a payment to a loan shark. The facial expressions she captures mange to be far more haunting than the butchered bodies.

Battaglia’s fight for legitimacy in a male-dominated professional environment makes for entertaining viewing, though it’s really the images themselves that do much of the talking. She is louche and confident, and just a short time in her company reveals why she was able to succeed. Like so many of the women in Longinotto’s previous work, Battaglia understands that she cannot remain passive while local crime kingpins murder with impunity, and so she decides to pivot to activism by setting up exhibitions of her work which force people to deal with the glum reality of this situation.

Longinotto has long been an advocate of the idea that we sometimes need to be confronted by violence to know the best way to fight it, and with that in mind, Battaglia seems less like a subject than she is a sister in arms.

The film gradually shifts away from profiling this pioneering woman in order to tell the more well-known story of the Italian government’s high-wire attempts to incarcerate various Mafia bosses. This includes extraordinary video footage of the so-called 1986 Maxi Trial which took place over six years and led to the indictment of 475 mafiosi. As a postscript to all this, various Italian judges working for the prosecution were killed (along with family members) by hired goons.

This switch to straight Mafia history certainly makes for compelling viewing, but it’s almost as if Battaglia has been forgotten, and a male-focused story takes the limelight. She narrates much of the tale, but it’s no longer about her. It’s perhaps the first time Longinotto has profiled a person who is no longer doing her job, and nostalgia isn’t her strongest suite.

The post Shooting the Mafia appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments