This story is part of Creative Resilience, an editorial series produced in collaboration with Squarespace.

“It’s so important in this day and age not just to think about going green, but to actually do it. The fashion industry is responsible for so many hazardous chemicals being used, so much environmental destruction, I just felt that I had to make a change.” Like so many people working in the film and television industry, the global pandemic has forced Jo Thompson to pause and take stock. As a costume designer with more than 30 years experience and a wide range of credits, from This Is England to Fleabag, she’s acutely aware of the sustainability issues facing her trade. She believes that now is the perfect time to start rewriting the playbook. “It seems completely absurd to spend thousands and thousands of pounds on one item of clothing,” she says, “especially when there are plenty of other means of sourcing materials and making clothing.”

Born and raised in Doncaster, South Yorkshire, Jo relocated to Nottingham (via Nigeria) to study before eventually settling in South London. After graduating university in the mid-’80s with a degree in theatre design, she quickly realised that staying on her chosen career path would be more difficult than she had anticipated. “My early work, especially during college, was very political,” she recalls, “quite often with a feminist slant. That’s really what I wanted to be doing, but I couldn’t sustain a living in London. There was just no money in it. So I ended up just working for free, doing lots of fringe theatre, very small-scale stuff where I would make everything from the costumes to the sets. I actually got a cleaning job for a time to supplement my income.”

Using colours harnessed from the natural things around you embeds an ethical approach

A placement at the famed agitprop theatre company 7:84, founded by the British playwright John McGrath, enabled Jo to further hone her craft and politics (the company’s name was taken from a statistic, first published in The Economist in 1966, that seven per cent of the UK’s population owned 84 per cent of the country’s wealth). From there, she landed a gig as a dresser at the London Palladium, which led to her being accepted onto a training scheme at the BBC. This comparatively corporate environment didn’t always agree with Jo, but she saw it as her passport to the world of film, which had always been her ultimate ambition. The four years she spent being nurtured creatively by Auntie proved invaluable. “At that time [at the BBC] it was fairly common to start an entire production literally from scratch. If you were doing a period drama, say, you’d be given the budget to have a work room and to get things sourced and dyed and printed. That scheme doesn’t exist any more, so I was very lucky really. It was a very hands-on, practical way of working, and I suppose what I’m doing now relates back to that same process.”

Jo’s big break in film came in 2006 when she was hired to work on Shane Meadows’ BAFTA-winning skinhead drama This Is England. “I’d heard they were looking for a costume designer,” she remembers, “so I reached out to Warp Films, the production company, and they set up a meeting with Shane. Luckily he knew my work already, because I’d already worked on lots of TV projects, commercials and short films by that point, so he just wanted to meet me to make sure we would get on. We met in Nottingham and sat outside on a step for about an hour, chatting about the world. This Is England was great because I got to do a lot of hand-dyeing and bleaching. It’s quite a stylised film, and there’s a really strong colour palette running throughout it. It was very creative and collaborative. Also, coming from the North, it very much reflected all the tribalism, the subcultures and the labels that were around when I was growing up.”

Sketching is as much a part of Jo’s process as the idea itself.

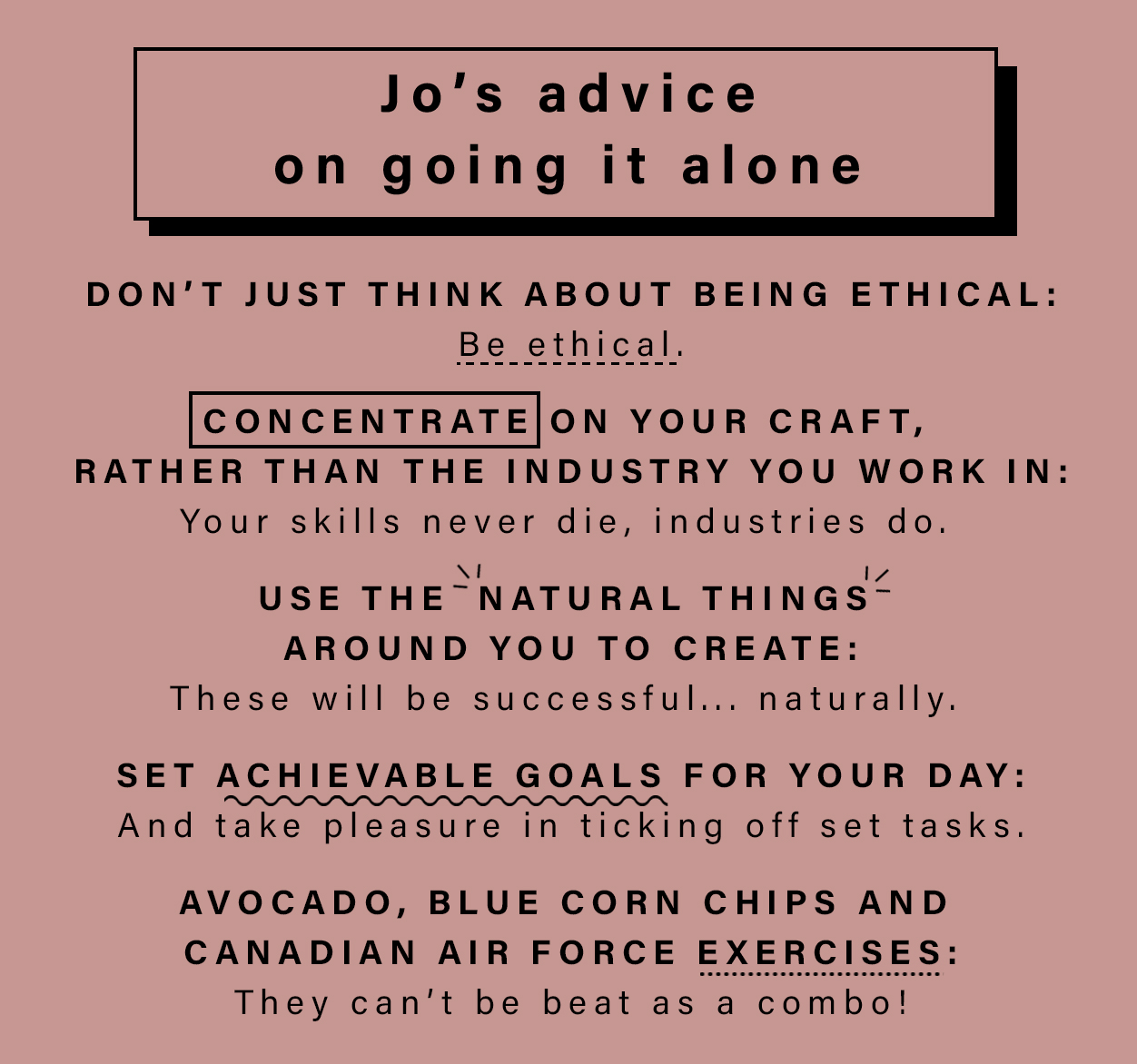

Given that she describes her favourite projects as those which allow her to collaborate closely with a writer/director, how has Jo found working in isolation over the past few months? “I’m so used to being surrounded by people every day, so it’s been quite strange suddenly having nobody around. I know it’s been the same for a lot of people, but when your work is usually so collaborative it’s difficult to adjust to another way of working. Actually, I quite enjoyed the early part of the lockdown, just having more time to do the things I’m not always able to fit into my day. At first, I set myself a task: to do one drawing every day. But that became quite boring after a while. I kept thinking to myself, ‘This is my chance to do something I’ve always wanted to do – don’t waste it.’”

The creative world that Jo inhabits is firmly analogue – steeped literally in physical texture and colour. Yet the rise of the digital world has facilitated her own creativity. “I really am not an expert in the internet or building websites – far from it!”, she says… “but with the Squarespace website building format and all the templates you can use, it’s really easy to image the site as a portfolio and to just stop messing about and publish your work.” And in the film industry, visibility is crucial, of course. “My Squarespace website is more than just a folio for me too. It’s a way to share work with other creatives and to get feedback on the work itself. It helps to confirm that you’re doing good stuff and that people like the direction in which you’re travelling – which when you’re flying solo is really important.”

The tactile nature of hand dyeing adds yet another layer to a deeply creative process.

It says a lot about Jo’s creative instincts and general outlook on life that not only has she managed to adjust during lockdown, she’s also developed a new way of working – one she hopes the rest of her industry will embrace once normal service has resumed. Harking back to her days at 7:84 and the BBC, she’s been experimenting with different dyeing techniques using naturally-derived colours. “I do a lot of dyeing in my work,” she says, “so I thought that if I’m spending all this time at home, why not use what’s readily available. The one rule I gave myself was that it had to be something I already had in my kitchen, so it’s using things like avocados and coffee, or hibiscus flower tea or black turtle beans.”

As a lifelong vegan, Jo has always been environmentally conscious, so in one sense moving away from using synthetic dyes feels like a natural progression. “I’ve been doing a lot of reading up about my industry recently, and it’s terrible the amount of waste that’s produced. I always try to use fabrics from ethical sources, but it’s not always easy. You’re trying to challenge the conventional way of doing things, which has been the same for a very long time – even though we’ve been using natural dyes and animal dyes since the Egyptians.” Jo admits that the natural dyeing process is very slow, but says she’s already thinking about how her homespun methods could be factored into a typical production schedule. “It’s definitely achievable.”

The camera hates synthetic fabrics – for Jo, the use of sustainable products makes creative sense.

There’s not just an ethical advantage to using organic, sustainable products. “I find that the camera hates synthetic fabrics,” Jo says. “The red dress in Peter Strickland’s In Fabric, for example, could have been made with a cheap mixed fibre, but the beauty of the silk is that it’s much more subtle on camera – even though it’s bright red – and it absorbs the light much better. The softness of it, the way it floated, you wouldn’t get that with a man-made fibre. Because film production is such a pressurised environment – it’s all about money and time – it’s quite hard to put into practice, but it’s been good to think about projects I’ve worked on previously, like In Fabric, and question how I could have done that more sustainably.

Prior to lockdown, Jo had just completed work on another Warp Films project, Little Birds, a six-part series adapted from Anaïs Nin’s collection of erotic short stories, which is due to air in August. While film and TV production in the UK is slowly starting up again, Jo accepts that it could be a while before things are back to business as usual. Good thing, then, that she plans to continue finding new ways to be creative and keep busy. “I want to reinvent cross-stitch next,” she says, “not doing twee little birds and flowers, but skulls and that sort of stuff. The thing that lockdown has brought home to me is that I need to have something else which doesn’t necessarily involve filmmaking. If something like this were to happen again, I need to have a back up.”

Jo Thompson and all of the creatives featured in our Creative Resilience series use Squarespace as an easy and affordable website builder to get their work out there in a beautiful way. If you’re thinking of sharing your own vision with the world, start building your Squarespace website today with a free trial – no credit card required! Use the discount code LWLies when you’re ready to go live.

Read more stories from our series on Creative Resilience, in partnership with Squarespace.

The post The costume designer dyeing to make film more sustainable appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments