When Sally Ride was going to become the first American woman to go to space in 1983, NASA engineers hit a wall with a question that baffled them as much as any equation. How many tampons should they send with her for a one-week mission? They number they landed on was 100.

Alice Winocour’s third feature, Proxima, continues a conversation about the very real legacy of astrophysicists and engineers and their struggle to accommodate female astronauts. Eva Green plays Sarah, an ambitious single mother to Stella (Zelie Boulant-Lemesle).

At the beginning of Wincour’s film, Sarah’s life-long dream of going to space is finally going to happen and she’s chosen to join the Proxima Mission to the International Space Station. It means months of gruelling training at the European Space Agency in Russia before lift-off and then separation from her daughter by the long dark reaches of space. But there’s no hesitation: this is what Sarah has been working towards her whole life so Stella goes to live with her astrophysicist dad (Lars Eidinger).

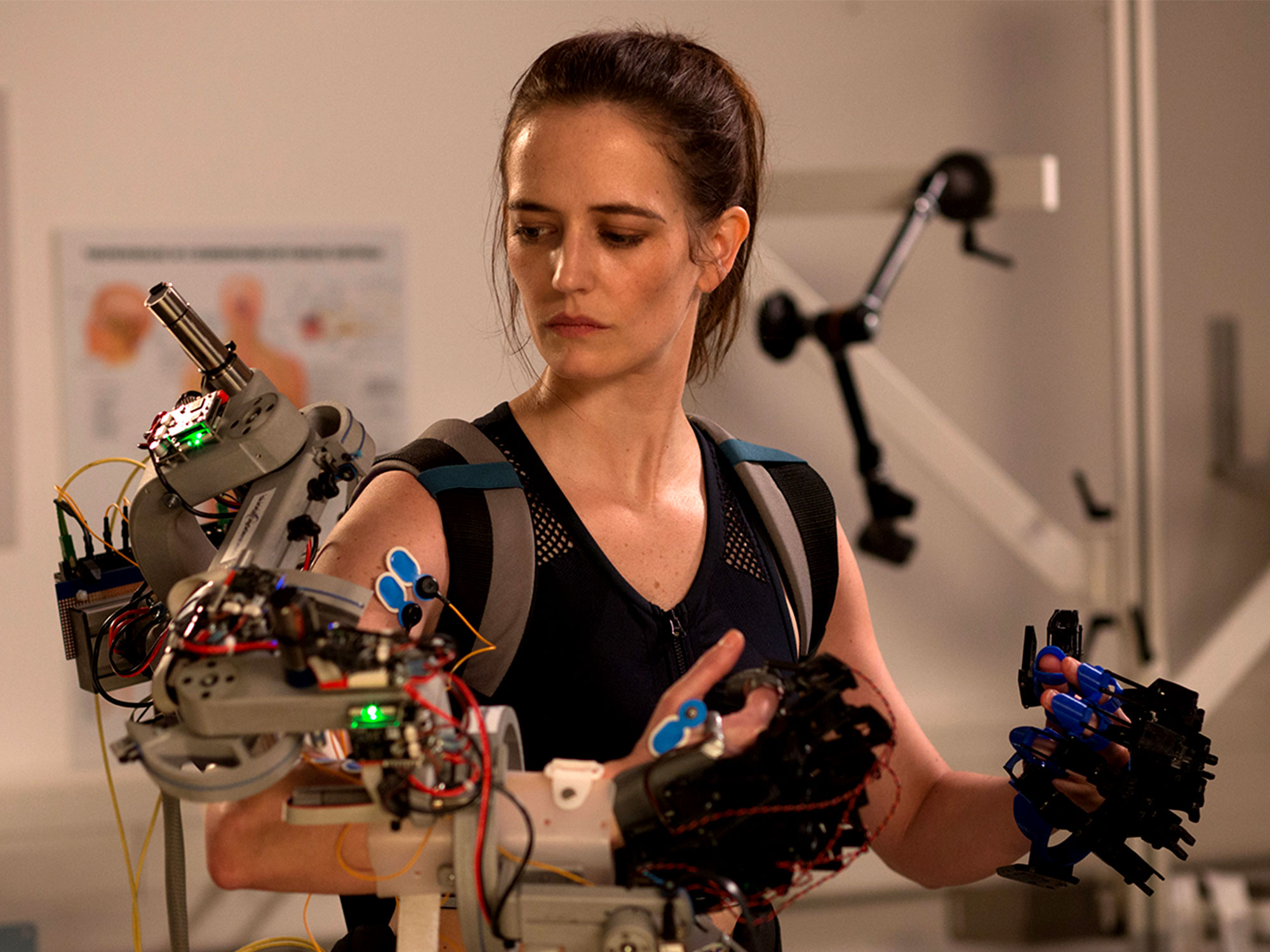

Proxima draws an easy comparison to James Grey’s Ad Astra – both films about the loss of a parent to the darkness of space – but think less glossy science fiction and more grounded realism for Winocour’s film. Shot by French cinematographer Georges Lechaptois at a real training facility, Sarah’s world at the ESA is all metallic monochromatic blues and greys. There’s an emphasis on the tactile day-to-day life of a training astronaut, with close-up shots of helmet buckles, clips and switches.

While Sarah gets to grips with the mechanics of getting to space, she also has to deal with her teammates: the supportive Russian, Anton Ochievski (Aleksey Fateev) and the chauvinistic American, Mike Shannon (Matt Dillon), who is less enthusiastic she’s joined them. At their first meeting, Mike jokes to the room that Sarah will make a fine addition to the team because he’s heard that French women are great cooks.

At training, he advises Sarah take on less preparation before suggesting she’s a space tourist, dead weight on his mission. While she’s batting away sexist macro and microaggressions in her male-dominated workplace, Sarah’s relationship with Stella is threatening to spin out of control as parental promises keep being broken. Green is at a career-best as the stoic Sarah, simultaneously determined and on the edge of breaking. So often hamming it up in Tim Burton roles, you forget just how exceptionally subtle she can be.

It would sell Proxima short to suggest the film is simply a dilemma of career versus motherhood. Rather the film is about two things from two perspectives. For Sarah it’s about saying goodbye and for Stella it’s about losing her mother. It’s a melancholic film that takes its time to get to its farewell, less showy than bigger budget parent-in-space flicks like First Man and Gravity, but no less moving. And unlike these films, Winocour makes the decision to never bring us to space. We’re left on the ground with Stella as her mother flies into the unknown and the loss is devastating.

The post Proxima appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments