Satyajit Ray is not missing from world cinema’s history books, but as an Indian and a student of the arts, it is almost comical for me to admit that I had never engaged with his cinema before this summer. This was for many reasons, none good enough, except maybe one that betrays a sense of envy – I am not Bengali.

In June, a summer break from my post-graduate degree was fast approaching. A student of performance and society, living away from home for the first time in my twenty-one years of life, in one of the busiest and most happening cultural capitals of the world, I decided to immerse myself in the city’s offerings. There is no feeling that matches the one you get when you walk out of the National Theatre after enjoying a particularly brilliant play all by yourself, onto the Southbank as the sun sets, and you realise you really are in London.

It was during one of these visits that I noticed a big orange billboard next to the BFI entrance, with the face of a young Shabana Azmi plastered over it – one of my favourite performers, and a darling of alternate Indian cinema. The words ‘Satyajit Ray,’ were written above her. I quickly took a picture to send to my fellow fans back home.

I knew then and there, that if there was ever a right time to get into Ray, it was now. On the British Film Institute’s website, I found a season of Satyajit Ray films curated by Sangeeta Dutta, playing well into August. It was the thematic curation of ‘The Big City’ that secured my interest in finally tackling Ray. Titles like Mahanagar (The Big City) and Seemabaddha (Company Limited) were the lures but it was Teen Kanya and the Apu Trilogy that officially made me a Ray devotee.

At the time that I was growing up in India, there was not much access to subtitled regional films for wider audiences, and if a dubbed version were to be made available, I would run in the other direction. I stated earlier that I find my illiteracy in Ray’s cinema ‘comical’, because, by the time I was watching films in languages I did not speak, I was almost intimidated by the idea of finally watching Ray’s work. All the great and wonderful things I’d learned about his place in the world of cinema made me unsure of whether I would actually be a ‘good audience’ for his ‘type of cinema.’ I had enough cinephile and filmmaker friends that it felt easier to say I hadn’t watched his work, rather than potentially admit I didn’t get it. This is funny to me now because – I have found his films to be my biggest source of comfort for the entirety of this hot, listless time in London.

The first Ray feature film I watched was Pather Panchali (The Song of the Little Road) at the beginning of July. From the simplicity of its depictions to the seeds of minute details planted in the first part of this trilogy, everything was a powerful reminder of a home that exists not in a place but in the past. The innocence and mischief of early childhood are Ray’s playthings, but so are the more heavy moments of grief and tragedy.

At no point in his films are any characters separated from the story of the world at large, no matter their place in it, and that is precisely the message Ray leaves his audiences with. The cycles of life and death, love and grief, victories and losses are their own characters in his stories, given the time and space to play out an intricate visual choreography on screen, elevated by Pandit Ravi Shankar’s musical contributions.

While Pather Panchali is an honest, and evocative first act about roots and what memory and nostalgia truly constitute, the second part Aparajito (The Unvanquished) is a tale of being faced with life’s elements that take us away from this, focusing instead on time, ambition, and all the novel realisations that come with questioning one’s identity and place in the world, finally beyond the confines of the home one has always known.

Inevitably Aparajito deals with the grief of losing all external ties to the home – first in the form of migration, and then in the form of his last remaining parent’s death for Apu. Karuna Banerjee’s Sarbojaya, Apu’s mother, is a raw and refreshing portrayal of motherhood, unapologetic in its hardships.

At the time of the second installment’s release, it was not well-received amongst the Bengali middle classes. The reason for which even Ray acknowledged was the popularity of films like Mother India, which glorified motherhood as the ultimate sacrificial ideal of superhuman tolerance and flawless devotion. A realistic portrayal of a mother-child relationship fraught with friction was not exactly welcome with audiences populating cinemas for easy escapism. But that was precisely why I found it refreshing – because such authentic portrayals are still rare occurrences in Indian Cinema.

Yet it was the last act in the saga, Apur Sansar (The World of Apu) that achieved what most finales in any medium fail to achieve – a resolution that doesn’t shy away from admitting that climactic moments are only a juncture. The film demonstrates that there are precious, fleeting moments of life that hold immense value, but does not contain any romanticised notions of improbable everlasting satisfaction. Instead, Apur Sansar is an acknowledgement of sufficient contentment being found in an array of such moments.

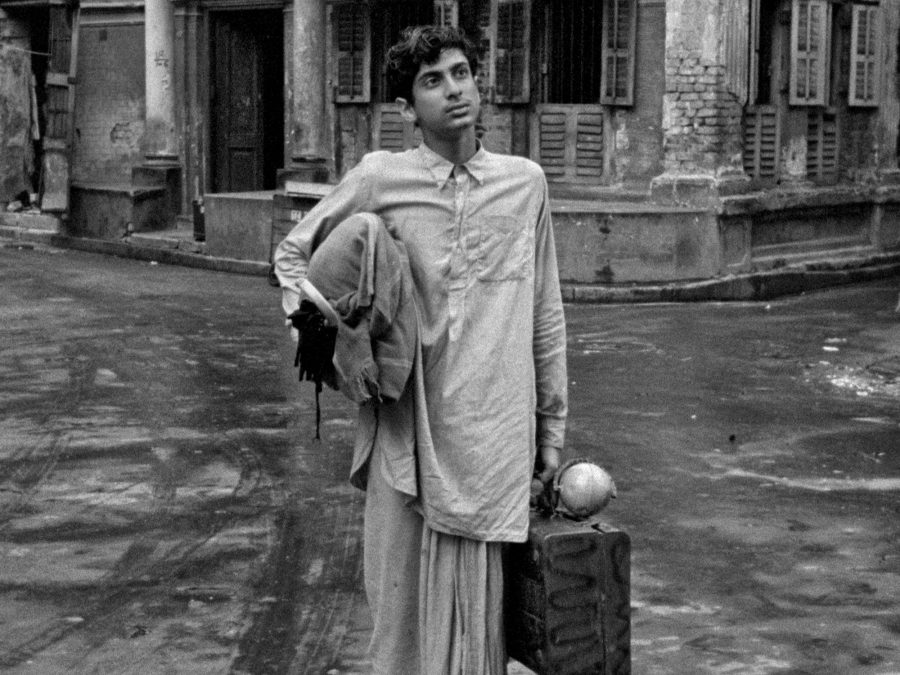

Mahanagar literally translates as ‘The Big City,’ and it deals brilliantly with this theme in the context of family, morality, and a woman’s affirmation of her selfhood. But what stood out for me in Apur Sansar’s depiction of everyday metropolitan life was the way in which an unanchored youth floats about life itself, knowing his way and losing it sometimes. The shots of Apu walking around the city, and the motifs that mark his path home to his rented room, are all such beautiful tributes to the rhythms of big city life. When his neighbour asks him at the beginning of the last film why he receives no mail, it is a heartbreaking moment as the audience remembers the happenings of the previous two films, and in a flash we spot that remembrance in Apu’s demeanour. Then, just as quickly, he moves on.

This is only one of the many ways in which Ray made these films about no one person in particular, but about everyone. The entirety of Pather Panchali and Aparajito culminates in the actions and choices the protagonist makes throughout Apur Sansar. And it is a story about exactly that– the responsibility of making the choices we do make. This hit home in more than one way, not least in a particular scene of banter between Apu and his dear friend Pulu, on the railway tracks they cross at night to go back to Apu’s rented room in the city. Apu’s passion for writing and a sense of his own journey is evident. The discussion between the two friends about whether one has to experience love to write about it, or whether imagination can suffice in such an endeavour, resembled a conversation I had had with a fellow creative friend myself.

It is also Ray’s only film where he has explored romance in his own penchant cinematic language of subtlety and depth, Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore being absolute delights to witness as Apu and Aparna. Keeping in mind how wary he was of using labels with his own idol, Jean Renoir, Ray has been termed a true humanist, and this is most obvious once you dive into his work. The Apu trilogy is more than just a coming-of-age saga executed well – it is an essential query into the nature of human existence and what gives it meaning.

There is a very special rasa (meaning nectar or flavour) – one that can only be described as a flavour of joy – in witnessing Ray’s mastery in an actual cinema with other people around to share it with, strangers or otherwise. I doubt I will ever again experience the kind of lasting giggles, bemused laughs, audible gasps and striking silences that accompany the Apu Trilogy in the BFI. It is an experience that reminds you of the power of the purest kind of cinematic storytelling and makes you a better person for having experienced it.

When my screening of Apur Sansar concluded there was a round of applause in the cinema directed towards something ineffable. This was a film, after all, not a live production; not even a premiere or festival screening where anyone from the creative team was present in the hall to gather appreciation. In the end, I suppose what we felt was the aliveness of Ray’s films – it is as if you can smell the wild, rustic breeze of Bengal, and feel its coolness on your face, attesting to the magic Satyajit Ray has crafted.

The next half of the BFI’s Satyajit Ray season runs through August 2022.

The post A summer with Satyajit Ray appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments