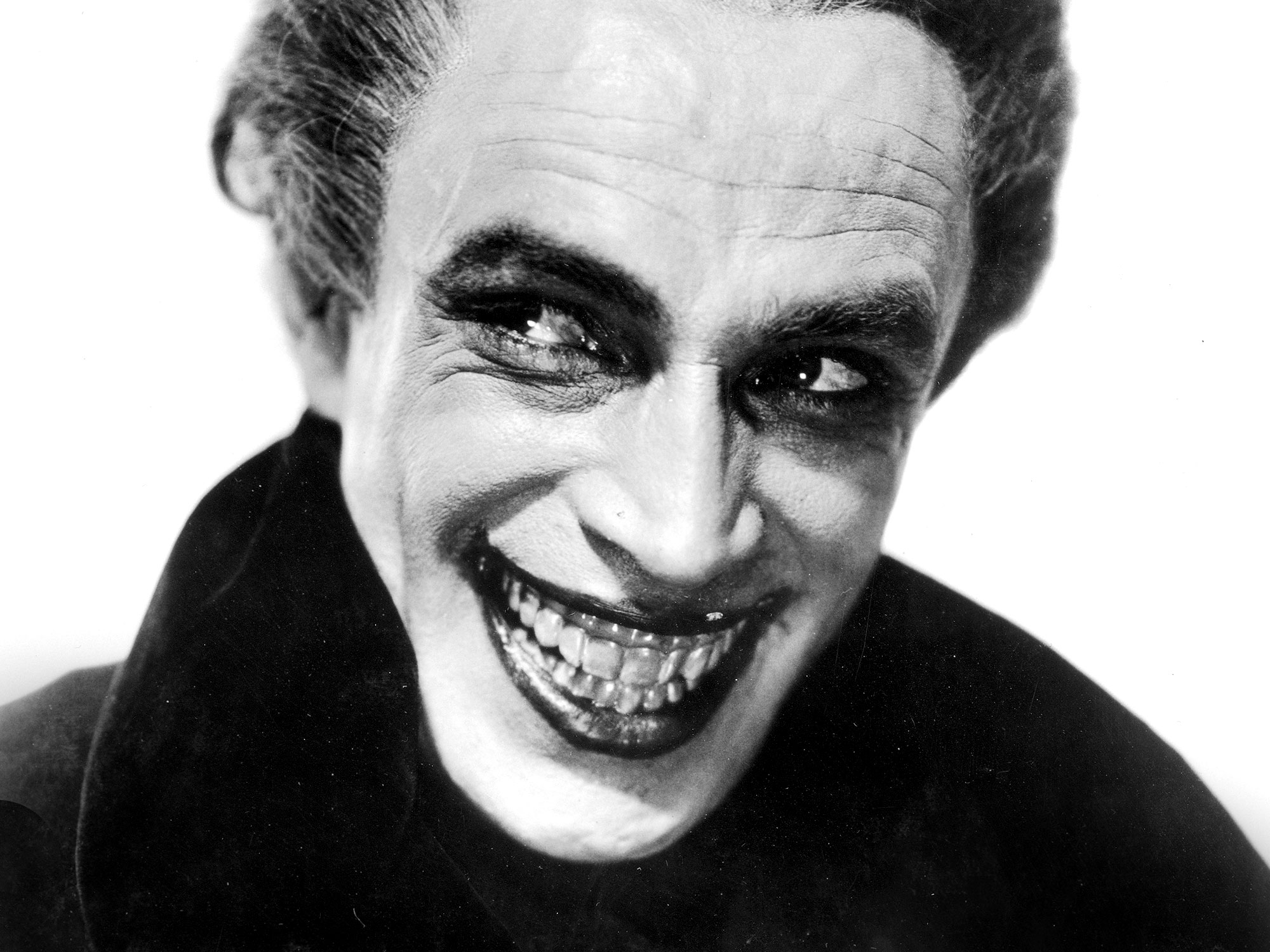

When popular stage clown Gwynplaine (Conrad Veidt), also known by his stage name ‘the man who laughs’, closes the cabinet housing his makeup mirror, we see clearly on either panel door a depiction of the twin masks of comedy and tragedy. This is at the Southwark Fair in London, during the reign of Queen Anne at the beginning of the eighteenth century, and those conventionalised masks – one smiling, one frowning – encapsulate the dual nature not only of the theatre that is Gwynplaine’s domain, but also of Gwynplaine himself.

The Man Who Laughs opens over a decade earlier with very different performer Barkilphedro (Brendon Hurst), the scheming, ambitious court jester to King James II (Sam de Grasse). “All his jests were cruel,” an intertext reveals, “and all smiles were false.” False smiles are all that Barkilphredo has in common with the sincere, sensitive Gwynplaine. For while Gwynplaine’s rebellious father Lord Clancharlie, who had refused to kiss James’ hand, has been in exile, the King has had the ten-year-old Gwynplaine’s mouth surgically misshapen into a grotesque grin, “so he might laugh forever at his fool of a father.”

Lord Clancharlie (also played briefly by Veidt, but with a frown that contrasts with his son’s permanent smile) returns for Gwynplaine, only to be killed by the King in the iron maiden, while the young boy, left for dead, has the good fortune to fall in with the kindly traveling impresario Ursus (Cesare Gravina) and another young orphan, the blind girl Dea.

As adults years later, Gwynplaine and Dea (Mary Philbin) have an act that is the toast of the town, but Gwynplaine’s rictus, while making him a perfect clown, conceals a deep sadness. For the very quality that allows him to raise a laugh onstage incurs ridicule outside of the auditorium – and his deep sense of shame about his appearance is an impediment to his love for Dea, even though she neither can see, nor cares, what he looks like.

When Gwynplaine’s forgotten genealogy catches up with him, Queen Anne (Josephine Crowell) decides to elevate him to the House of Lords and to marry him off to the promiscuous Duchess Josiana (Olga Baclanova) to legitimise the Duchess’ occupation of the late Lord Clancharlie’s estate. Now Gwynplaine must decide whether to embrace Josiana and the establishment, or to rebel and stay – or indeed leave – with Dea and Ursus.

In keeping with much of the film’s setting amid the stalls, rides and freak show exhibits of Southwark Fair, The Man Who Laughs is ruled by what Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin would term the “carnivalesque”: this is a topsy-turvy world where masked aristocrats cavort with drunken “ruffians”, where a lowly, disfigured clown can be inducted into the House of Lords (“It’s outrageous!”, as one peer complains) and where Ursus (named for the Latin word for ‘bear’) has a pet dog called Homo (Latin for ‘human’).

In this theatricalised space where the boundaries between social ranks and even species are readily transgressed, Gwynplaine is the ultimate embodiment of the carnivalesque – a man who is his own mask – while only his blind beloved Dea can see through the vanities of class and cadre to a more substantial underlying nobility.

If its characters keep switching between high and low, happy and sad, The Man Who Laughs also comes with a certain intermediacy in formal terms. Made in 1928 on the threshold of the Talkies, the film is silent, with its dialogue rendered through intertitles, while also boasting an innovative monophonic Movietone score with occasional synchronised sounds (bells, knocks, trumpets) and even the murmuring hubbub of crowds and a romantic song.

The Man Who Laughs is perhaps most famous now for the influence of Gwynplaine’s unusual facial features on the manically grinning iconography of the Batman’s comic book nemesis The Joker, or of the titular lead in William Castle’s Mr Sardonicus. Such comparisons, however, will inevitably lead to false expectations of this film’s narrative content and themes. Better simply to marvel at Veidt’s performance, as he displays a full emotional range for his character despite being unable to move what is normally one of the face’s most expressive parts.

Adapted from Victor Hugo’s 1869 novel of the same name, The Man Who Laughs might set itself up to be a spiritual sequel to Wallace Worsley’s influential 1923 horror The Hunchback of Notre Dame (also adapted from Hugo). In both, a monstrous but innocent hero becomes embroiled in an erotic tangle and a clash of class in a capital city. Yet despite initial references to unconventional surgeries and deadly torture, Leni’s film never really displays the kind of horror found in his other features like Waxworks and The Cat and the Canary, but is rather a sentimental romance and a political satire, with just a smidgin of rooftop swashbuckling thrown in near the end.

In keeping with the smiling and frowning masks displayed on Gwynplaine’s mirror cabinet, The Man Who Laughs is certainly a tragicomedy. But where Hugo’s original ultimately veered towards tragedy, Leni’s prefers a happier, more hopeful ending that will leave a smile on the face of the viewer. The real tragedy here, of course, is that Leni died the year after this was made.

The Man Who Laughs is available in a 1080p presentation on Blu-ray from Universal’s 4K restoration, as part of Eureka Video’s Masters of Cinema Series, on 17 August.

The post How The Man Who Laughs redefined early horror cinema appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments