Harry Caul has crawled under a hotel room sink. His legs are pulled up to his body, and his head is tilted as he grasps his headphones like a lovelorn man listening to break-up songs. It’s the sounds of conversation he hears on the other side of the wall – close, but miles away. Cradling himself in a foetal position, his distant stare cuts through the quiet as he does what he is paid to do: he listens.

Few actors capture the burden of loneliness like Gene Hackman. His characters have a marooned quality, as if the weight of the world has severed them from the rest of humanity. In Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, he’s fiercely brilliant as the tyrannical sheriff “Little Bill” Daggett; equally memorable is his turn as Harry Moseby, a detective sinking deeper into a mystery as dark as the sea at midnight, in Arthur Penn’s Night Moves.

Hackman’s most remote character is Harry Caul, the protagonist of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 film The Conversation. A private surveillance expert who is as much as voyeur as an artist, he is unable to reconcile the dubious morality of his work. The job requires invisibility – the targets can’t know their conversations are bugged – but it’s Harry’s shame that drives his need to disappear from view.

Coppola’s sparse dialogue pushes Hackman’s physicality to the foreground, a performance communicated almost through mime. After a stakeout, Harry arrives home to find a birthday present left by a neighbour. He calls her to ask how she gained access to his apartment, while he unceremoniously unbuttons his trousers and wriggles out of them (wriggling out of his own skin might be preferable). He sits in his underwear and shirt, his clothes and body an extension of his own paranoid, itchy discomfort.

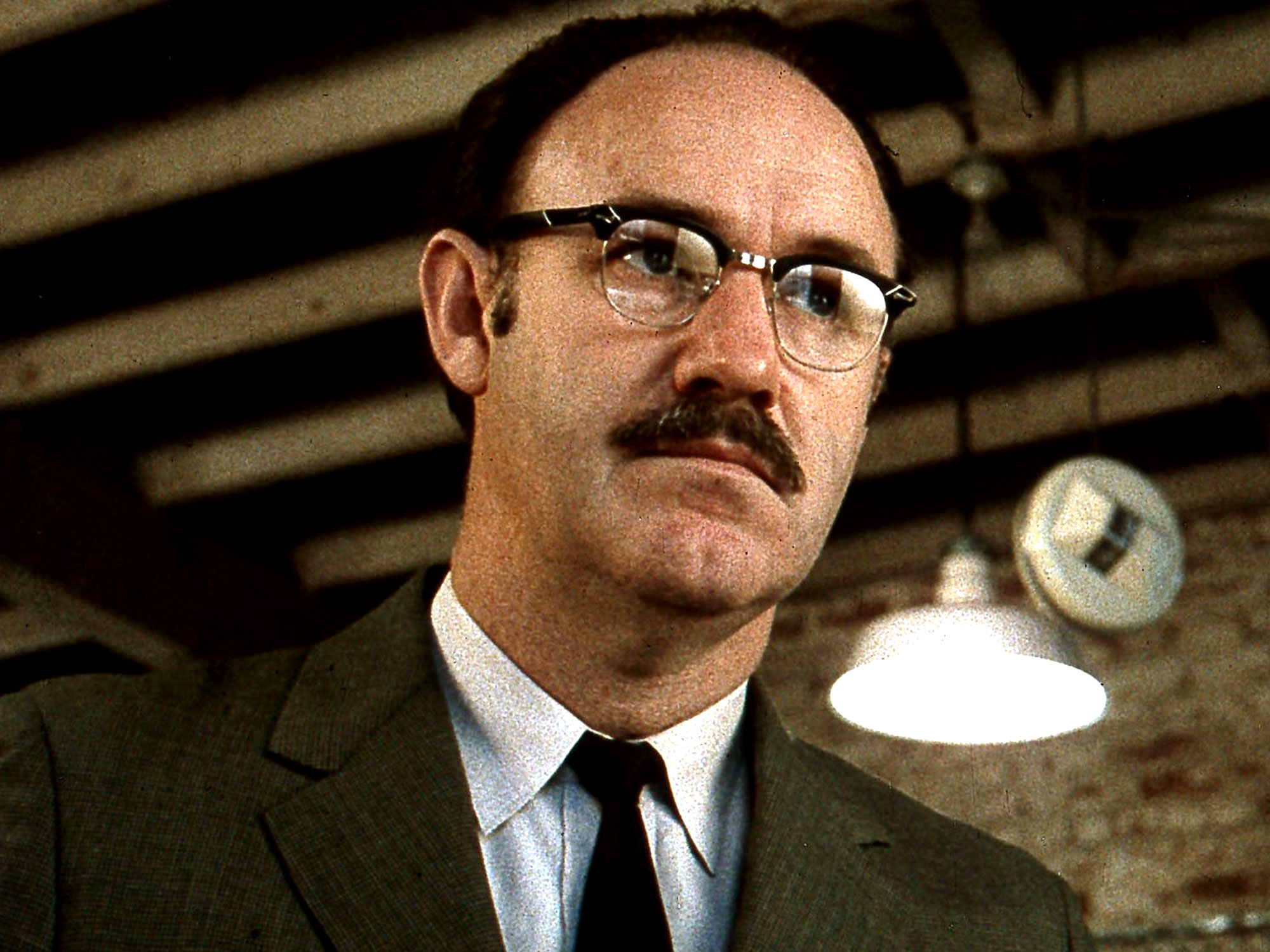

Rarely is Harry shown without his translucent rain mac, a layer separating him from anything undesirable, be it bad weather or other people. Thick eyeglasses reflect the world he’s desperate to keep out, while a moustache obscures a perpetually sweaty upper lip. There is nothing sexy or stylish about this spying. When he does speak, it’s in stammered half-sentences: fumbling, awkward and punctuated by long, frightened stares.

Only when admiring his own work is there a hint of pride. In a pivotal scene, Harry sits behind colossal machinery, playing back and editing several recordings he’s made of a clandestine conversation. The film’s narrative tension is predicated upon this recording, though now the danger of its contents is irrelevant. Now he is a maestro, elegant in his movements.

He manipulates the machinery like the conductor of an analogue orchestra. His hand movements are fluid and confident, a gentle smirk appearing behind the moustache. Morals don’t seem to matter in the instant that you betray them, as long as you betray them with flare. Harry doesn’t need to talk or think – he just needs to perform, and perform loud enough for the fears to be drowned out.

So, how can this be the same man that we find curled up on the floor of a hotel bathroom? Intermittent gratification does little to prevent the tidal wave of guilt crashing down on him. You can practically see Hackman shrink in the moments when he reckons with what he’s done. “People were hurt because of my work,” he whimpers. It’s his own twisted version of post-coital clarity and regret, and now people are getting hurt again.

The dichotomy of pleasure and remorse that Hackman balances reflects the fears of our own work-based culture: if we come to define ourselves by the quality of the work we do, then who are we outside of that work? That tension is there in Hackman’s darting eyes, his restless body. Gazing at his feet or some arbitrary piece of his clothing, he holds himself with an awkwardness that gives away his greatest fear: that he could be under surveillance. He seems both rigid and small, as if he were a tape caught in a larger machine that just won’t spit him out. He craves release; to dissolve into nothingness.

Anonymity might well be the best Harry can hope for, to be permanently obscured in the San Francisco fog. Yet he’s not invisible. We catch his figure wading through the fog, his work following him like a ghost, along with our own current fears about social media, privacy and isolation. Like editors, we assemble Harry’s glances and gestures into an understanding of who this man is, just as he takes garbled audio recordings of strangers and assembles them into conversations.

As joyfully complicit participants in the act of watching, perhaps we realise something about our own voyeurism, too. It is testament to Hackman’s skilled performance that, like the reflections that dance across his glasses, we’re looking directly at a distorted image of ourselves as much as we’re looking at him. We’re all lost in the fog: alone, together.

The post Why I love Gene Hackman’s performance in The Conversation appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments