The true story of Montgomery Clift, as told by his youngest nephew

About five years ago, filmmaking duo Robert Clift and Hillary Demmon Clift decided to make a documentary about Robert’s long-dead uncle. So the husband-and-wife team did what most people in that situation would do. They began the long process of interviewing relatives and collecting old audio, film and other snippets, trying to make sense out of the fragments they had. As with other long-dead uncles, there were as many whispered rumours and longstanding stories about the man as there were accepted facts. Except most people’s uncles aren’t Montgomery Clift.

“I grew up with people telling me who Monty was, but I didn’t know him,” Robert Clift tells LWLies. “I heard stories about him. I heard public accounts and private accounts of him, and I wanted to reconcile those two.” A leading man of near-mythical status, Clift film career went from strength to strength despite him being notoriously choosy with his roles. He starred as a social climber full of coiled rage opposite Elizabeth Taylor in A Place in the Sun, a hard-headed idealist who goes his own way in From Here to Eternity, a tortured priest in I Confess, and a Jewish GI during World War Two in The Young Lions.

Robert Clift is the son of Montgomery’s older brother, Brooks, making him the youngest nephew of the Hollywood icon. He never met the family’s most famous member, but he grew up regaled with stories, and with his father’s immense collection of artefacts he had stockpiled on Monty. As such, the story that unfolds in Making Montgomery Clift is as much about Brooks Clift and his dogged desire to protect the legacy of his kid brother – replete with his mountain of archives – and the ripple effect it would have on his family.

Brooks had the curious habit of recording everything, and kept audio of phone conversations with his brother. Previously unseen stacks of 16mm home movies were also uncovered by the filmmakers, making for a hauntingly intimate portrait of Clift’s more private moments. It’s this family backstory that gives real heft to the documentary, and a genuinely unique perspective.

Making Montgomery Clift is more essay film than staid biography, carefully deconstructing those decades of image-making around the star. It assumes some knowledge about Clift’s life and career, using Robert as a narrator to give a sense of his personal attachment to the story. “My curiosity is rooted in the discrepancy between what I heard at home and what was known in the public,” explains Robert. “And the idea of tracing the construction of his persona.”

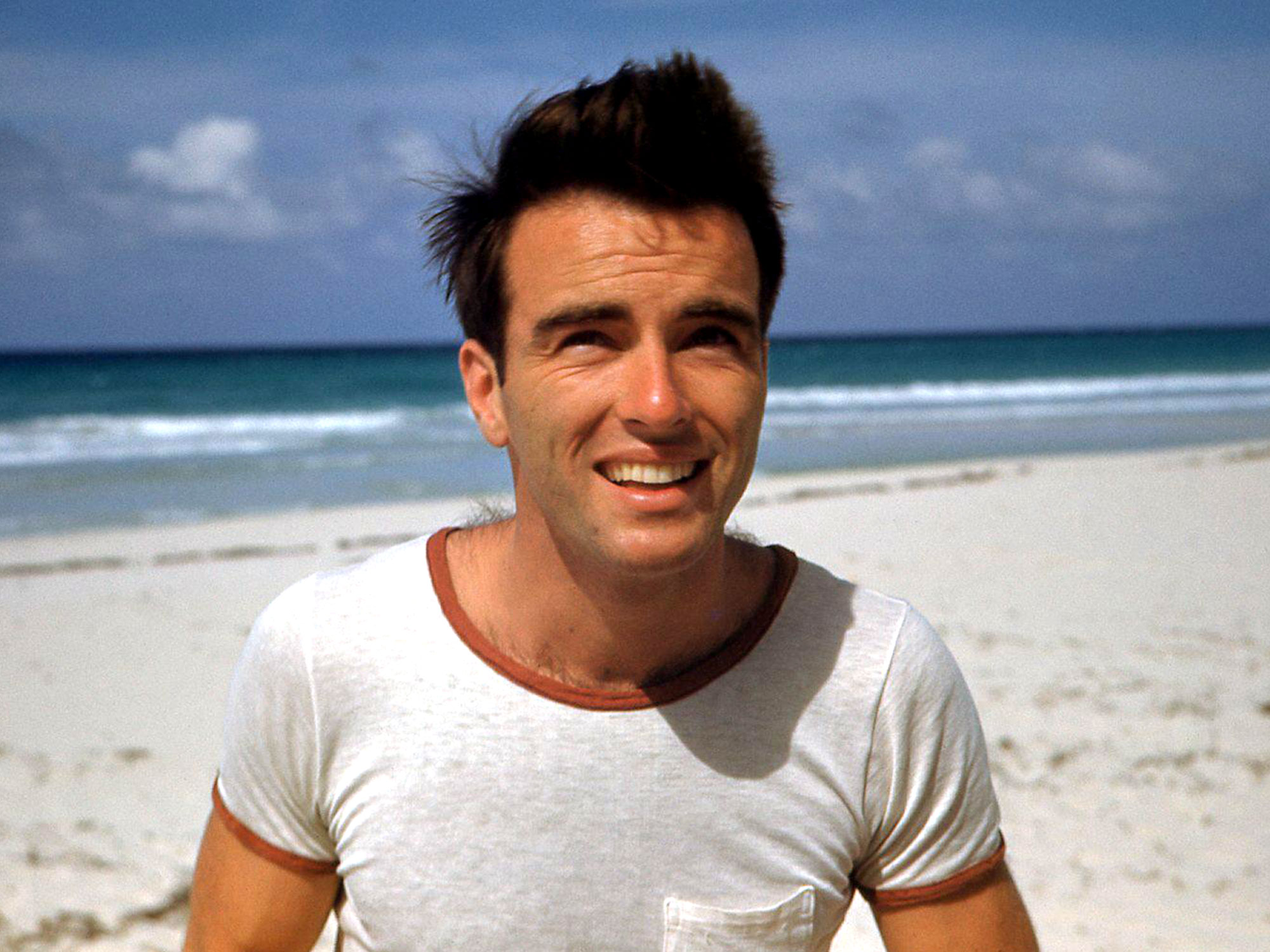

Part of Clift’s persona was immaculate good looks. He had a sculpted, rangy handsomeness, a profile too neat for approach and too delicate for machismo. The documentary informs us that he was often filmed in soft focus, something studio-era filmmakers tended to reserve for their leading ladies. In William Wyler’s The Heiress, a lovelorn Olivia de Havilland sighs: “Father, don’t you think he’s the most beautiful man you’ve ever seen?”

This physical beauty would be inexorably feed into the mythmaking around Clift, part of which revolves around what’s assumed to be a natural moodiness and vanity. In truth, Robert says, “Monty always put an emphasis on his labour as an actor – he refers to himself in one interview as a ‘worker’, which you don’t hear very much when talking about acting.” Hillary adds, “He had integrity. He had concerns, and wouldn’t do a part if they weren’t addressed. We wanted a chance to broaden the idea of who Monty could’ve been. We wanted to look at some of the elements of his life, like his labour in acting, that got overshadowed. Or misrepresented, overtaken by stereotypes.”

There are two pieces of accepted wisdom about Montgomery Clift. One is that he was a closeted gay or bisexual man who felt hugely burdened by his sexuality; the other is that his fateful car crash in 1956, which permanently scarred his face and left him in chronic pain, accelerated his alcohol and drug dependencies and seriously damaged his self-esteem. Both are widely thought to have contributed to Clift’s premature death of a heart attack in 1966, aged just 45. But Making Montgomery Clift resists this narrative, using unseen footage, audio, beautiful still photography and the odd interview to a paint a different picture.

In fact, he was reasonably comfortable with his sexuality, cheerfully dating both men and women. He was unabashed enough that people like John Wayne and John Huston made disdainful or homophobic remarks about him while working with him. Robert says of his uncle, “I feel his life has been defined through a lens that’s informed by outdated and homophobic ideas. I think that shifting that lens allows one to see his life from a completely different perspective.”

Clift had a buoyant, impish personality and was a constant practical joker, clowning around more often than he could be found brooding. Even his issues around chemical dependency began long before his accident, after adolescent illnesses left him with chronic issues. As for his looks being ruined? Not as much of an issue as biographers and writers have made it out to be.

This revisionism is much-needed. A quick Google search of ‘Montgomery Clift’ returns phrases like ‘beautiful loser’ and ‘longest suicide in Hollywood history’. He’s become the poster boy for tragedy in Old Hollywood, a story shaped by well-meaning but sensationalist biographies and oft-repeated anecdotes.

Still, it’s easy to fall into believing this time-worn narrative of the tragic star. The Clash certainly did when they wrote the song ‘The Right Profile’. (The title is a reference to the way the actor had to be shot by the camera in order to preserve his appearance post-accident.) Clift’s roles during this period of his career sometimes seemed to show a painful self-awareness of the changes to his appearance. In The Misfits, his busted-up rodeo star speaks on a payphone to his mother, mumbling, “Nah, my face has healed up fine.” And during a devastating cameo in Judgement at Nuremberg, as a man sterilised by the Nazis, he stutters and slurs and jabbers to the point that people assumed he was drunkenly ad-libbing about his own personal free-fall.

Rumours surrounding Clift’s mental condition at the time of production ruined this Oscar-nominated role for family members. “For so many years, I thought this is someone that my family loved and here he is having a mental breakdown onscreen,” reflects Robert. “I didn’t want to watch it, because that’s what I saw. Even though I was warned not to trust all the stories, no one went into detail, so I didn’t know what that meant. Now, in my forties, I can watch Judgement at Nuremberg and appreciate that performance as a performance.”

As deeply entrenched as the romantic concept of Clift’s brokenness may be, it obscures a far richer and altogether more lively picture of the man. It also has an unfortunate tendency to overshadow a movie star who was – regardless of his personal life – one of the finest actors of the 20th century. His sexually ambivalent, vulnerable characters were both revolutionary and ingenious; his influence invaluable to successive generations of actors. Making Montgomery Clift is an insightful labour of love that helps us to see that more clearly.

Making Montgomery Clift screens at the Glasgow Film Festival on 28 February and again on 1 March. For more info visit glasgowfilm.org

The post The true story of Montgomery Clift, as told by his youngest nephew appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments