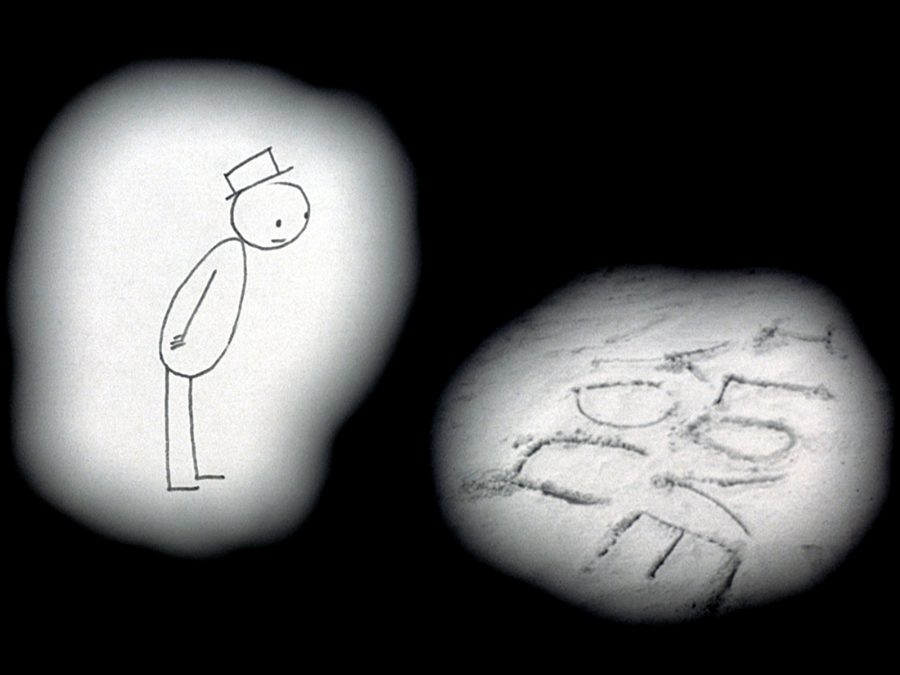

When you’re a film critic, people always ask, “What is your favourite film?”, and ever since 2013 I answer very quickly and easily: Don Hertzfeldt’s It’s Such A Beautiful Day. There are not many films that are shorthand for the genetic material of your soul. In my case, there’s only one. Although, technically, it’s three short films compiled into a single portmanteau feature animation, and it follows a hatwearing stick figure named Bill who is trying to live his little life against the backdrop of some medical bad news that is rooted in his family history. Maybe this doesn’t sound like much on paper, but its svelte 62 minutes covers all of life: the silly embarrassments; the absurd humour; the inherited suffering; the desire for love; the isolation; the yearning; the memories; the dreams.

I discovered the film at its 2013 run at London’s ICA cinema that kicked off with a special Hertzfeldt extravaganza night, co-compered by LWLies’ editor David Jenkins. They say don’t meet your heroes, so it’s a good thing that Don and I did this interview over email. In a bid to curry favour when I reached out to Don, I mentioned that I once went home with a man I met at a bus stop because he said (before I did) that It’s Such a Beautiful Day was his favourite film. Don wrote back, “I might require that your bus stop anecdote appears in the finished article.” A deal was struck. Now over to him.

LWLies: It is so very touching how small and inglorious Bill’s life is, and yet you give him the soaring classical treatment. Who is Bill to you? How did you decide what music would soundtrack his life?

Hertzfeldt: The big music that plays when Bill has his first epiphany, and everything begins to turn to colour is traditionally performed as a piano piece. It’s Rachmaninoff. I first heard the unusual full orchestra version that was used in the movie during the Winter Olympics. It’s this epic piece. A girl came out skating to it. She’d been hyped up as the person to beat in this competition and had all of her big jumps timed to the really explosive moments in this music. But on her first jump, she fell. And she kept falling. And the music kept going and the bigness of the music just made it more and more tragic. She just kept falling.

When I find the right music, like finding a new idea, again something clicks and it’s like I have no choice. That’s it, that’s going in a movie. I wanted to use big beautiful operatic cues for Bill’s story because everyone’s life, even when nothing much is going on, is still full of beauty and small moments that can feel just as big to someone as any big romantic murderous subplot in a melodrama. Just looking at the right tree can be a big operatic moment for somebody. I think there’s also this sad sense of urgency and inevitability to so many of the pieces I ended up choosing. Like a deep feeling of missing out, of another life that’s always just around the corner but you can never get there.

Is the tragicomic tone of the film a fair representation of your outlook?

Probably, or at least my outlook from 10 or so years ago. Large chunks of the movie were lifted from my old diary. When I’d hit a wall while writing I’d go through my diary again to see if there was anything else to steal. I’m not Bill, but we were both living in cramped apartments in our late 20s, so many things seemed to cross over easily.

Can you narrativise the origins story of It’s Such a Beautiful Day?

In 1999, before the big dot-com crash, there was a new media company that asked me to do a comic strip for their website. They said I could keep all the rights to it and they’d pay the rent on my apartment for as long as I did the strip. And I said, that sounds like a pretty good deal to me. So, I started drawing these comic strips and out of them came this one recurring character. All my characters looked more or less the same so I put a hat on him. The strips weren’t very good but they had a sort of weird quality to them because there weren’t really any punchlines. At the time I was sort of interested in the idea of an anti-comic strip, where maybe nothing funny even happens.

It would just be Bill walking around doing this or that, and then sadly going home again and that’s it. So this website didn’t last very long, and maybe it was my fault, but this character stuck with me. And why was he wearing this hat, really? Maybe he’s self-conscious because he’s got no hair. But he’s not very old, so what happened to his hair? Or maybe he’s got some scars he’s covering up. Did he have a couple of brain surgeries? I worked on

some other things but these ideas floated after me for five more years and in 2005 they sort of burst out all at once and I started work on Everything Will Be OK.

“I don’t know if we always fear death itself as much as the feeling of being Oskar Schindler at the end of the movie, saying, “I could have done more, I could have done more.””

How long was that entire process?

From Everything Will Be OK to It’s Such a Beautiful Day was about six years to write, animate, and shoot. Maybe a little more. The form you work in – and the number of jobs you do for it – is so labour intensive.

What keeps you going?

If I ever feel sad during a production it’s never from actually animating – animating is very much like a different state of mind, like emotionless concentration – but the side effect of working for months and months can begin to feel like you’re just a hamster on a wheel. Every day has a sameness to it, you wake up, get back on the hamster wheel, you run and run, eat hamster food, and go back to sleep. And the outside world can really start to seem like it’s moving in fast motion and totally passing you by as you run in place every day.

But then you step out of the wheel and think, wait a minute, I totally forgot this hamster wheel’s been connected to this battery. And running on the wheel every day has been generating this tremendous amount of energy, and look how it’s all been adding up. This little wheel has made this movie, that movie, this thing, that other thing, allowed me to travel here and to there, and on and on. The movies that have come out of this still seem so much bigger than the work. It still feels like some kind of miracle.

Were there specific cultural properties (a song, a movie, a quote) that kept you on track during the making of It’s Such a Beautiful Day?

There’s wasn’t a specific single thing that kept me on track, but music in general’s always been a really important driving force. If I can’t listen to music while I animate, I’ll get sad. I’m confused when I meet someone who isn’t particularly interested in music of any kind. How is such a thing possible? When I was animating in school, after so many months I began to buy armfuls of used cassette tapes for 50 cents from the record shop down the street, literally anything, I didn’t care what it was, I just needed anything new to listen to as I kept working. I do think many random song lyrics have found their way into the writing over the years. I don’t remember when I noticed this, but for instance if you look at the lyrics to R.E.M.’s ‘You Are The Everything’, that’s maybe It’s Such a Beautiful Day right there.

I read that in creating Bill’s ailment you were careful not to make it too specific in order to make it more of a Rorschach ailment that people could see themselves in. What did you draw from to create it, and what is the art to making an illness seem familiar but not too familiar?

Right, I didn’t want to tell the audience, okay he has this rare thing with this long Latin name, and give people that exit ramp: “Well, thankfully this will never happen to me.” I don’t want to put it in a box, but if we were to very generally say the movie is about dying, then the “How” is ultimately not really that important. The how is just details. What’s more important is, “What are we actually going to do with this knowledge?” I also liked the idea that maybe the audience doesn’t know what’s wrong with Bill because Bill just doesn’t remember. We only know what Bill knows, and he’s very confused.

So, I researched a particular neurological issue and worked backwards from there: what sort of tests would they give him? What sort of memory problems would he have? How do we make this feel grounded, compared to the fantasy stuff happening in his head? I think I was also getting a little annoyed with mental illness in movies always meaning someone’s either a screaming murderer or a delightful quirky genius who eats peanut butter with a spoon, like it’s a sort of stupid superpower, and I wanted to do something that felt more honest. We see that a lot of Bill’s suffering is inherited, and that there is a history of mental illness in his family. Did he ever have a chance for things to go any way other than the way they did? No, I don’t think so. There’s all sorts of images of forces of nature in I Am So Proud of You that seem to suggest his fate is just the way things are.

Do you fear death?

Sometimes. I think I’m more bothered by the idea of running out of time before I’m ready, like a rude or sudden interruption. I don’t know if we always fear death itself as much as the feeling of being Oskar Schindler at the end of the movie, saying, “I could have done more, I could have done more.”

How motivated are you by the thought of how people will receive your work? I ask because it’s so personal that it feels like a very deep communication and I wonder if you send it out in the hope of receiving a specific kind of response?

I think probably not at all. I try not to let it cross my mind. Whenever I begin to think about how something might be received or how many people might be watching, it’s sort of paralyzing. It’s the only time I start to feel what would be described as a creative block. Wondering about the audience a lot can be a sort of poison. The only thing I want to focus on with the audience in mind is clarity. Just making sure I’m not getting ahead of myself, not making something confusing or overly complicated, or losing the audience by picking the wrong angle or something. The director’s most basic job is clarity. Clarity is my favourite word. And then, if you’ve done the best job you could, whether or not the audience likes the movie is more their problem.

Your work creates a very emotional type of fandom, with people hurling their confessions your way. Do you know what to do with those intimate confidences?

I try to be a good listener. But the movie is really the thing that’s there for people when they need it, I’m just the dope who made it.

It’s Such a Beautiful Day is available on Blu-ray via bitterfilms.com and viewable online via Don Hertzfeldt’s Vimeo channel.

The post It’s Such a Beautiful Day at 10 appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments