Why Millennium Actress remains one of cinema’s greatest love letters

Of the numerous indelible works Satoshi Kon made throughout his career, Millennium Actress might be the only one that looks to our past. Following his 1997 debut feature Perfect Blue, the Japanese animator and manga creator began to make predictions about the changing relationship between people and media in the fledgling digital age – his third film, Tokyo Godfathers, looked at those who fell through the cracks in contemporary Tokyo, and this theme carried through to his TV series Paranoia Agent and final film Paprika, too.

Millennium Actress was Kon’s follow up Perfect Blue. Just as both films lie on opposite sides of the line between the 20th and 21st centuries, their construction and themes mirror one another. While Perfect Blue is more empathetic than cynical, it reflects the grim potential of the internet in its subjective psychological horror. Though tinged with melancholy and tragedy, Millennium Actress uses cinema history to turn the reality-bending drama of Perfect Blue into something more gentle and romantic, finding the beauty in that thin divide between media and the self, rather than encroaching horror.

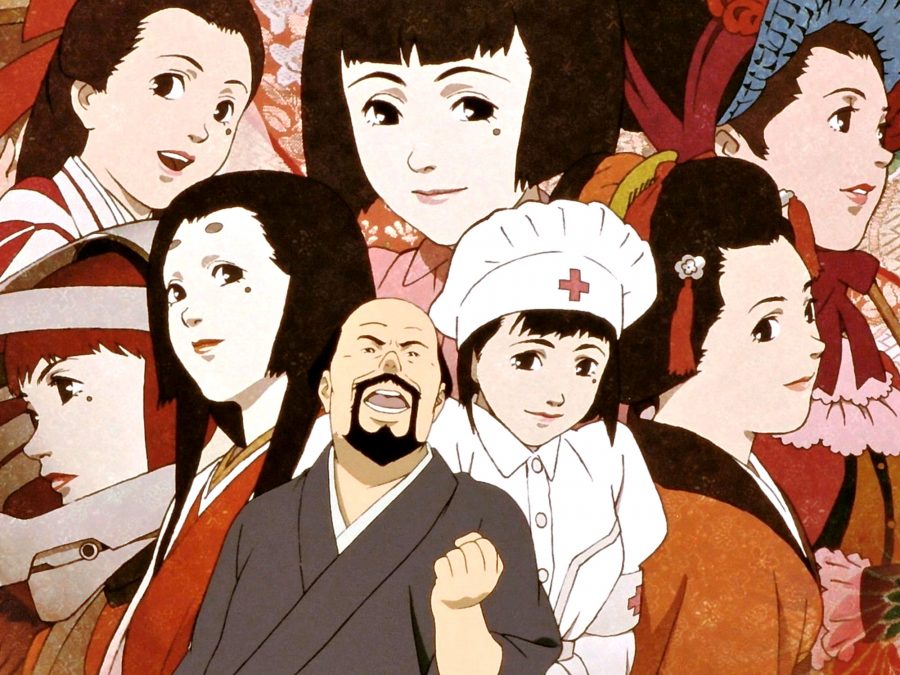

The set-up is simple enough: a documentarian named Genya Tachibana is looking to interview the reclusive actress Chiyoko (who appears as an amalgamation of Setsuko Hara and Hideaki Takemine), the former star of a studio whose original lot is being demolished at the film’s opening. Once they begin the interview, the film leaps back in time to Chiyoko’s childhood, telling of the beginning of her acting career and her search for an illusive man whom she sheltered from the government.

It would be a fairly straightforward premise if not for the fact that in the recounting of her story, Genya and his cameraman appear conspicuously within Chiyoko’s memories as if they were there, filming and interfering. Furthermore, as they witness the beginning of her acting career the line between Chiyoko’s performances and her real life blurs until it’s hard to tell which is which.

Kon and co-writer Sadayaki Murai convey the emotional reality of her life through a restaging of 20th century Japanese cinema. The crew follows Chiyoko across different time periods (and genres) in scenes referencing Gojira and Zatoichi, a set that combines Akira Kurosawa’s Shakespearean epics Ran and Throne of Blood, and a confrontation between Chiyoko and her mother which echos Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story. Each new homage corresponds to a relationship in the real world.

Among its gorgeous and ever-changing background art, Takeshi Honda’s subtle and realistic character design helps to ground the fantastical plot, while Susumu Hirasawa’s bouncy electronic score reminds us that we are always standing outside of the various time periods which the characters jump between. (As for this new release, All The Anime’s restoration is pristine; the colours pop and the drawings are sharper than ever, without sacrificing the original texture.)

Cinema acting as a love letter to itself is hardly a novel idea, but outside of Kon’s own filmography there is nothing quite like Millennium Actress. The director masterfully uses the malleability of animation to find new beauty in even the most well-trodden ground. Kon paints film as almost spiritual in the way it prolongs life, and although the format itself is also perishable, Chiyoko’s life and memory stretch from one millennium to the next.

Millennium Actress is available now via All The Anime.

The post Why Millennium Actress remains one of cinema’s greatest love letters appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments