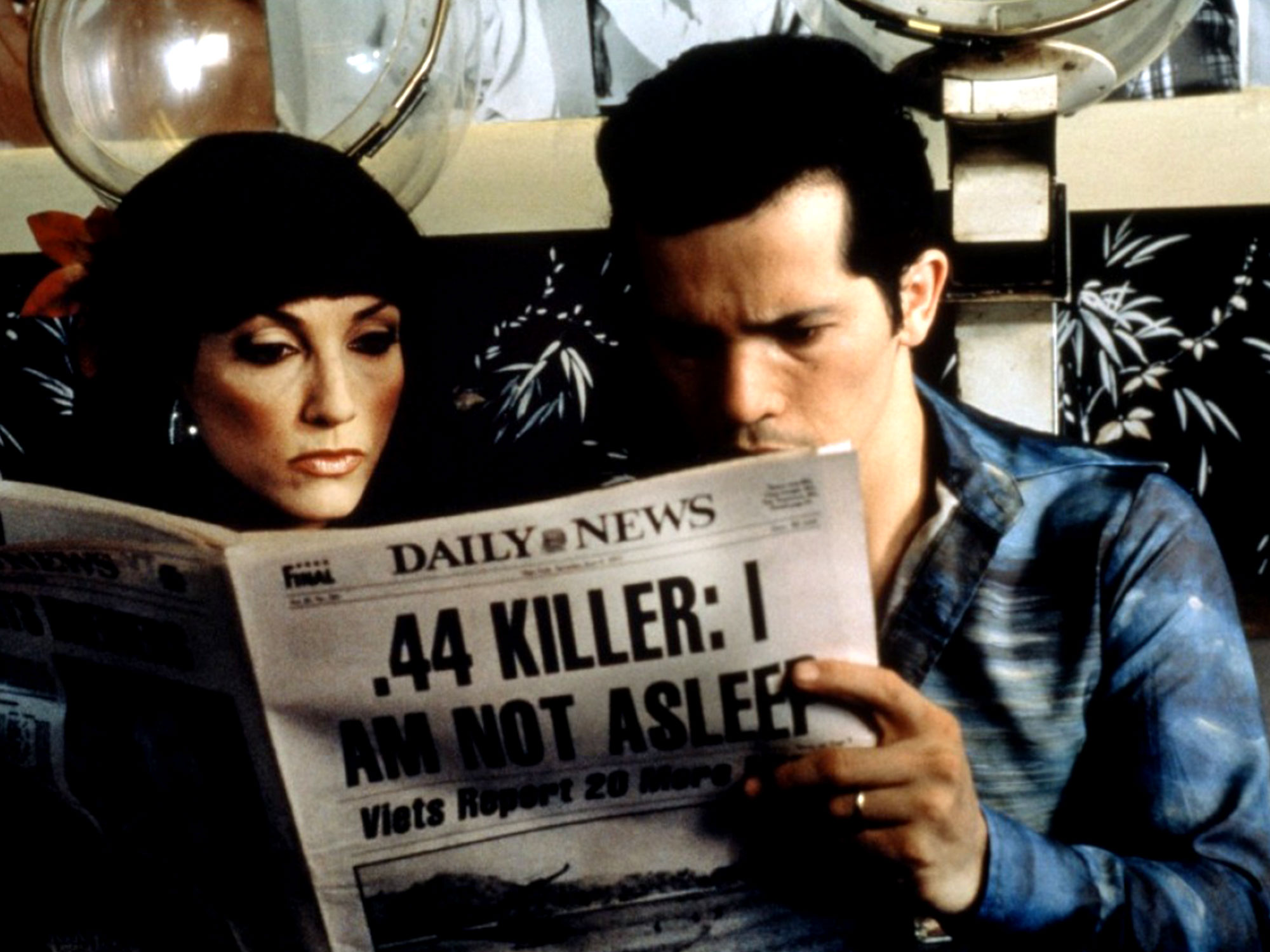

It’s the hottest summer on record and a killer is on the loose. This is New York during the summer of 1977, and a heat wave has descended on the city like a thick cloud. It was a once in a lifetime meteorological event that felt biblical; almost destined. As New Yorkers drifted through the heaviness of humidity, they were terrorised by a killer known as the Son of Sam who, using a .44 calibre Bulldog revolver, murdered six people and injured seven more. On 3 July, 1999, Spike Lee released Summer of Sam, a reflection on that fateful summer.

The film follows two young men from a predominantly Italian-American section of the Bronx. Vinny (John Leguizamo) is a serial adulterer trying to save his marriage with Dionna (Mira Sorvino) and Ritchie (Adrien Brody), a childhood friend who has reinvented himself as a punk. As events unfold over that long, hot, historic summer, we watch as their lives intersect with death, irrevocably shaping their futures.

Lee is no stranger to heat. Ten years before Summer of Sam he made Do the Right Thing, in which racial tensions rise as the mercury soars on the hottest day of the year. It was a breakthrough film that announced the young director as a major new voice in American cinema. Summer of Sam deals with a lot of the same ideas, but unlike Do the Right Thing it struggled to find a critical audience. Reviews were mixed, many choosing to focus on the film’s cynicism and graphic portrayals of sex and violence.

What is immediately striking about Summer of Sam is how its characters are compelled towards self-destruction. The Son of Sam has already killed by the time the film begins and early on Vinny has a brush with him; he’s in the back seat of his car with his wife’s cousin when he almost becomes a victim of the spree killer. It’s a moment Vinny takes as a message from God to reform his adulterous ways. Yet in spite of this close call, it does very little to dissuade him from going out at night and bringing his wife along with him.

If a killer was on the loose, what would you do? In a city as big as New York, it seems unlikely that you would ever run into him – but what if the environment around you is succumbing to growing paranoia. People know he targets couples in cars, especially young brunettes, so women play at dress-up. They put on blonde wigs and become someone else. The women, rather than embody fear, seem to float on air, taking pleasure in the displacement of their real selves. It is as if their new hairstyle not only protects them against death but gives them permission to indulge in their true desires.

This duality becomes a source of pleasure and conflict. Vinny struggles with his fidelity because he can’t bring himself to think of his wife as a sexual being. To touch her the way he’d touch her cousin or one of his salon employees would reduce her to a whore, an image he cannot abide. Rather than try to become intimate with her in order to overcome his sin, he works to repress all desire.

Leguizamo gives a performance of pulsating nerves. Undeniably sexual, he leans into machoism but feels uncomfortable in self-reflexivity. His aggression is always threatening to explode, but there is so much tenderness as well.

Relatively sexually explicit for a mainstream release, the film leans heavily into intimacy rather than gratuitousness. Even flings feel raw, embodied with a certain animalistic realness. In his relationship with his wife though, Vinny can’t let go and experience real intimacy without ruining the image he has of her in his mind. He is unable to be his true self, which leads him to question his identity entirely and violence sparks in his need to reaffirm his sense of self.

Ritchie, meanwhile, becomes increasingly sexually liberated. In a film of dualities, if Dionna is the virgin, Jennifer Esposito’s Ruby is the whore. When she shacks up with Ritchie, the pair become increasingly adventurous and find comfort in their shared otherness. Ritchie’s new punk persona has alienated him from his clean cut, Catholic upbringing, and her reputation as being “easy” has similarly cast her as different. Both maintain kindness and love, but their choices alienate them and put a target on their backs amidst rising tensions of humidity and the Son of Sam’s continued rampage.

In spite of his own sins, Vinny becomes increasingly aggressed by his sexual frustration and Ritchie’s apparent liberation; so does the rest of the neighbourhood. This is where the film’s cynicism digs deep. As the characters begin to mirror the aggressive patterns of the killer at large, they follow the lines of their own bias. In asking women to wear wigs, stay indoors and be “good”, they are trying to control the uncontrollable. When they say Ritchie purposefully turn his back on those ideals, they resent his freedom and channel their repressed rage towards him. The film’s startling finale, in the aftermath of the David Berkowitz’s arrest as the Son of Sam, is a harrowing example of mob mentality justice. One that not only works to reinforce the status quo but violently exemplifies the demons of repression and hate.

How can you not be cynical in a society that is so unfair? For all the attempts to control safety and comfort, the world doesn’t offer much consolation. The systems in place – be it religion, the justice system or democracy – are often the sources of deep anguish and suffering. Characters reaching for opportunities they can’t get at collectively traumatised not only by the Son of Sam but by society itself. In a sense, this is Lee’s obsession: legacies of trauma passed down. Even if the status quo is often weaponised against the citizenry, for most, it is worth upholding as a way to maintain some semblance of self often through violence and self-annihilation.

The post Revisiting Summer of Sam – Spike Lee’s other great heatwave movie appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Forest Essentials [CPV] WW](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/pcw-uploads/logos/forest-essentials-promo-codes-coupons.png)

0 comments